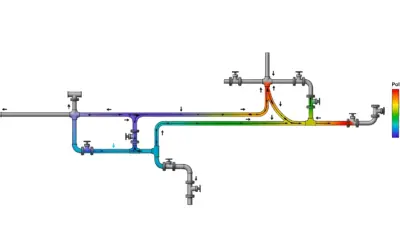

Pressure Profile Analysis: Discharge Pipeline

Context: Discharge PipelineA pipeline carrying pressurized fluid from a pump to a destination point. Design for a Water Supply System.

You are a junior civil engineer tasked with verifying the design of a water supply line. The system pumps water from a lower reservoir to an elevated storage tank. Understanding the pressure profile along the pipeline is crucial to ensure the pipe pressure rating is not exceeded and that positive pressure is maintained throughout the system to prevent contamination.

Pedagogical Note: This exercise will guide you through the calculation of the Hydraulic Grade Line (HGL)A line representing the sum of the pressure head and the elevation head.. You will apply the Bernoulli equation extended with friction losses (Darcy-Weisbach) using US Customary units.

Learning Objectives

- Calculate fluid velocity and Reynolds number in a pipe.

- Determine the Darcy friction factor and calculate major head losses.

- Apply the energy equation (Bernoulli) between two points.

- Calculate the pressure at the pump discharge and intermediate points.

Study Data

System Specifications

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Fluid | Water at 60°F |

| Kinematic Viscosity (\(\nu\)) | \(1.217 \times 10^{-5} \text{ ft}^2/\text{s}\) |

| Specific Weight (\(\gamma\)) | 62.4 lb/ft³ |

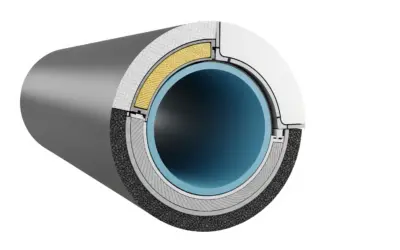

| Pipe Material | Commercial Steel (\(\epsilon = 0.00015\) ft) |

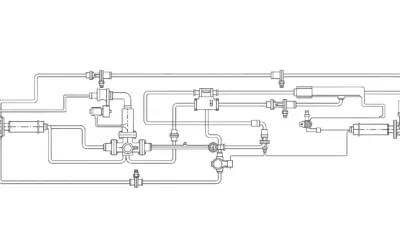

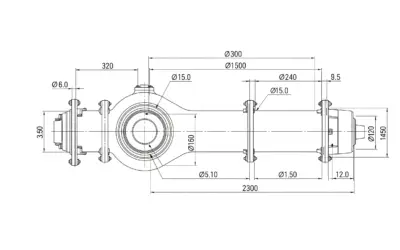

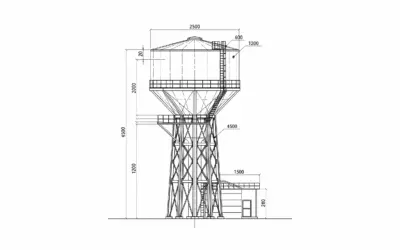

System Schematic

| Parameter | Symbol | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flow Rate | \(Q\) | 400 | gpm (gallons/min) |

| Pipe Length | \(L\) | 2000 | ft |

| Pipe Diameter | \(D\) | 6 | inches |

| Discharge Elevation | \(z_{tank}\) | 150 | ft |

Questions to Address

- Convert the flow rate to cubic feet per second (cfs) and calculate the flow velocity.

- Determine the Reynolds number and the Darcy friction factor (\(f\)) using iteration.

- Calculate the major head loss (\(h_f\)) due to friction in the pipe.

- Calculate the pressure required at the pump discharge (Assume \(z_{pump}=0\)).

- Calculate the pressure at Point A (Midpoint, \(L=1000\) ft, Elev. 75 ft).

Fundamentals of Pressurized Hydraulics

To solve this problem, we rely on the conservation of energy equation (Bernoulli) modified for real fluids by including head losses.

1. Bernoulli Equation with Head Loss

Between point 1 and point 2:

\[ \frac{P_1}{\gamma} + z_1 + \frac{v_1^2}{2g} + H_{pump} = \frac{P_2}{\gamma} + z_2 + \frac{v_2^2}{2g} + h_L \]

Where \(h_L\) is total head loss (friction + minor losses).

2. Darcy-Weisbach Equation

Used to calculate major friction loss:

\[ h_f = f \cdot \frac{L}{D} \cdot \frac{v^2}{2g} \]

Where \(f\) is the Darcy friction factor. For turbulent flow, it is often found using the implicit Colebrook-White equation.

Solution: Pressure Profile Analysis

Question 1: Velocity Calculation

Principle

Velocity is required for Reynolds number and head loss calculations. We first need consistent units (ft/s).

Mini-Lesson

Flow Continuity: In a closed pipe with incompressible fluid, flow rate \(Q\) is constant. The relationship is \(Q = A \times v\), where \(A\) is the cross-sectional area and \(v\) is the mean velocity.

Pedagogical Note

Always convert all units to the base system (ft, s) before starting any calculation. 1 cubic foot approx. equals 7.48 gallons.

Norms

Typical design velocities for water supply mains range from 2 to 5 ft/s to minimize head loss and prevent water hammer.

Formula(s)

Continuity Equation

Hypotheses

The fluid is water (incompressible). The pipe is full (pressurized flow).

Data

| Parameter | Symbol | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flow Rate | \(Q\) | 400 | gpm |

| Diameter | \(D\) | 6 | in |

Tips

Don't forget to divide the diameter by 12 to get feet! \(6 \text{ in} = 0.5 \text{ ft}\).

Schematic (Before Calculations)

Visualizing the cross-section.

Pipe Cross-Section

Calculation(s)

Step 1: Unit Conversions.

First, we need to convert gallons per minute (gpm) to cubic feet per second (cfs) because the velocity must be in ft/s to be consistent with acceleration due to gravity (ft/s²). We use the conversion factors \(1 \text{ ft}^3 \approx 7.48 \text{ gallons}\) and \(1 \text{ min} = 60 \text{ s}\).

We now have the volumetric flow rate in compatible units (0.891 cfs). Next, we must convert the pipe diameter from inches to feet to match the flow rate units.

Step 2: Calculate Area (\(A\)) and Velocity (\(v\)). Now we compute the cross-sectional area of the pipe and use the continuity equation to find the velocity.

The resulting flow velocity is 4.54 ft/s. This value will be used in the Reynolds number calculation.

Schematic (After Calculations)

Visual representation of the velocity profile.

Velocity Profile

Analysis

The calculated velocity is 4.54 ft/s. This falls within the standard design range (usually < 5-6 ft/s), suggesting the 6-inch diameter is appropriate for this flow.

Cautionary Points

Confusing gpm (gallons per minute) with cfs (cubic feet per second) is a major source of error. Ensure your conversion factor is correct (1 cfs = 448.8 gpm).

Key Takeaways

- Always work in base units (ft, lb, s).

- Velocity is inversely proportional to the square of the diameter.

Did You Know?

Doubling the pipe diameter reduces the velocity by a factor of 4, significantly lowering head losses.

FAQ

Common questions:

Final Result

Your Turn

What would be the velocity if the flow rate was 600 gpm?

Memo Card

Q1 Summary: Continuity Eq: \(Q = Av\). Standard water velocity: 2-5 ft/s.

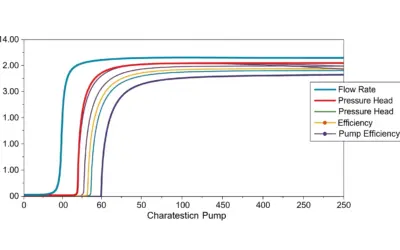

Question 2: Reynolds Number & Friction Factor (Iterative)

Principle

We calculate the Reynolds number to determine flow regime. For turbulent flow, we use the implicit Colebrook-White equation and solve for \(f\) iteratively.

Mini-Lesson

Flow Regimes:

- Laminar (\(Re < 2000\)): Viscous forces dominate.

- Turbulent (\(Re > 4000\)): Inertial forces dominate. This is most common in industrial water pipes.

Colebrook-White: The standard empirical equation for \(f\) in turbulent flow, connecting roughness \(\epsilon\) and \(Re\).

Pedagogical Note

The Colebrook equation cannot be solved algebraically for \(f\) because \(f\) appears on both sides (implicit equation). We must guess a value and refine it.

Norms

Commercial Steel roughness \(\epsilon\) is typically taken as 0.00015 ft (or 0.045 mm).

Formula(s)

Reynolds Number

Colebrook-White Equation

Hypotheses

Flow is fully developed and turbulent.

Data

| Parameter | Symbol | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kinematic Viscosity | \(\nu\) | \(1.217 \times 10^{-5}\) | ft²/s |

| Roughness | \(\epsilon\) | 0.00015 | ft |

Tips

A good initial guess for \(f\) in turbulent water pipes is typically 0.02.

Calculation(s)

Step 1: Reynolds Number (\(Re\)). We substitute velocity \(v=4.54\), diameter \(D=0.5\), and kinematic viscosity \(\nu\).

Step 2: Relative Roughness (\(\epsilon/D\)). This dimensionless ratio quantifies how rough the pipe wall is relative to its diameter.

Step 3: Iterative solution for \(f\). Since the Colebrook equation is implicit, we start with an initial guess \(f_0 = 0.02\) and compute the Right Hand Side (RHS) to find a better estimate.

Iteration 1: Guess \(f = 0.02\). Calculate the new value.

Now derive the new \(f_1\) from the calculated RHS: \( \frac{1}{\sqrt{f}} = 7.508 \Rightarrow \sqrt{f} = \frac{1}{7.508} \Rightarrow f_1 = (0.1332)^2 = 0.01774 \). This new value is significantly different from 0.02, so we must iterate again.

Iteration 2: Use \(f_1 = 0.01774\).

New \(f\): \( f_2 = (1 / 7.479)^2 = 0.01788 \). The value changed slightly from 0.01774 to 0.01788.

Iteration 3: Use \(f_2 = 0.01788\).

The value has stabilized at 0.0179 (rounded). We can stop iterating.

Schematic (After Calculations)

Location on Moody Diagram.

Moody Chart Position

Analysis

The Re is very high (>4000), confirming highly turbulent flow. The friction factor depends on both roughness and Reynolds number (Transitional zone of Moody Chart).

Cautionary Points

Ensure you use base 10 logarithm (\(\log_{10}\)) and not natural logarithm (\(\ln\)).

Key Takeaways

- Iterative methods are standard for finding \(f\).

- Roughness plays a key role in turbulent flow friction.

Did You Know?

The Moody Diagram is just a graphical representation of the Colebrook-White equation, created by Lewis Moody in 1944.

FAQ

Common questions:

Final Result

Your Turn

Calculate \(f\) if the pipe roughness was 0.0005 ft (Concrete).

Memo Card

Q2 Summary: Turbulent flow requires iteration for \(f\). \(f\) generally decreases as \(Re\) increases.

Question 3: Major Head Loss

Principle

Calculate the energy lost due to friction along the entire pipe length using the refined friction factor.

Mini-Lesson

Head Loss: Represents the loss of pressure energy converted to heat due to fluid viscosity. In long pipelines, friction (major loss) dominates over local losses (fittings, valves).

Pedagogical Note

Think of head loss as a "pressure tax" you pay for moving the fluid over a distance.

Norms

Acceptable head loss gradients often range from 0.5 ft to 5 ft per 100 ft of pipe length, depending on energy costs and capital costs.

Formula(s)

Darcy-Weisbach Equation

Hypotheses

Minor losses (entries, exits, bends) are neglected in this specific calculation step.

Data

| Parameter | Symbol | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Length | \(L\) | 2000 | ft |

| Gravity | \(g\) | 32.2 | ft/s² |

Tips

Velocity head \(\frac{v^2}{2g}\) is a recurring term. Calculate it once: \(4.54^2 / (2 \times 32.2) \approx 0.32\) ft.

Schematic (Before Calculations)

Energy Line Concept

Calculation(s)

We break the calculation into three distinct terms for clarity: the friction factor \(f\), the geometric ratio \(L/D\), and the kinetic energy or velocity head \(v^2/2g\).

The result tells us that 22.9 feet of head (energy per unit weight) is dissipated as heat while the water travels 2000 feet through this 6-inch pipe.

Schematic (After Calculations)

Visual comparison of energy.

Energy Budget

Analysis

A loss of 22.9 ft over 2000 ft represents about 1.1 ft loss per 100 ft, which is a reasonable friction slope for a transmission main.

Cautionary Points

Head loss is proportional to the **square** of velocity. A small increase in flow drastically increases loss.

Key Takeaways

- \(h_f\) is directly proportional to Length.

- \(h_f\) is inversely proportional to Diameter.

Did You Know?

In very old pipes, corrosion and mineral deposits can double the friction factor, drastically reducing flow capacity.

FAQ

Common questions:

Final Result

Your Turn

What would be the head loss if the pipe length was doubled to 4000 ft?

Memo Card

Q3 Summary: \(h_f = f(L/D)(v^2/2g)\). Friction converts pressure to heat.

Question 4: Pump Discharge Pressure

Principle

Apply Bernoulli between pump discharge (1) and tank surface (2). \(P_2 = 0\) (gauge), \(v_2 \approx 0\).

Mini-Lesson

Bernoulli's Principle: Energy is conserved. Energy added by the pump must overcome elevation difference (static head) plus friction losses (dynamic head) plus velocity head differences.

Pedagogical Note

We usually define the "System Head" as Static Lift + Friction Loss.

Norms

Pump casings are typically rated for 175 psi or 250 psi. Our design pressure must be checked against this.

Formula(s)

Hypotheses

Tank pressure is atmospheric (\(P_2=0\) psig). Tank surface velocity is negligible (\(v_2=0\)).

Data

| Parameter | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| Elevation Change (\(z_2-z_1\)) | 150 | ft |

| Specific Weight (\(\gamma\)) | 62.4 | lb/ft³ |

Tips

Pressure in psi = (Pressure Head in ft \(\times \gamma\)) / 144. (Since \(1 \text{ ft}^2 = 144 \text{ in}^2\)).

Schematic (Before Calculations)

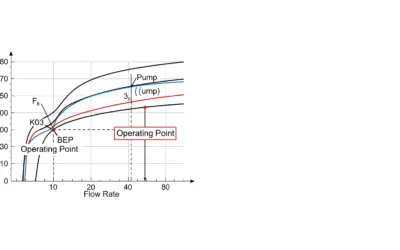

System Head Curve

Calculation(s)

Step 1: Rearrange the Bernoulli equation to isolate the Pressure Head term \(\frac{P_1}{\gamma}\). This represents the energy stored as pressure at the pump discharge.

Step 2: Substitute the known values. \(z_2 - z_1 = 150\) ft (Static Lift). \(h_f = 22.9\) ft (Friction Loss). Velocity head at the tank surface \(v_2\) is 0, and at pump discharge \(v_1\) contributes 0.32 ft.

Step 3: Convert Head (ft) to Pressure (psi) using the specific weight of water \(\gamma = 62.4 \text{ lb/ft}^3\). We divide by 144 to convert square feet to square inches.

The pump must deliver 74.8 psi to the water to overcome the elevation difference and friction losses.

Schematic (After Calculations)

Visualizing the components of pump pressure.

Pressure Components

Analysis

Most of the pump's energy (150 ft) goes to lifting the water. Friction adds about 15% (22.9 ft) to the requirement.

Cautionary Points

This calculates pressure *at the pump discharge*. It does not account for suction side conditions (NPSH).

Key Takeaways

- Total Dynamic Head (TDH) dictates pump selection.

- Static head is constant; friction head varies with flow.

Did You Know?

Pumps are sized based on the "System Curve", which combines the static lift and the friction curve calculated here.

FAQ

Common questions:

Final Result

Your Turn

Calculate pressure if tank elevation was 200 ft (assuming same friction).

Memo Card

Q4 Summary: \(P_{discharge} \propto \text{Elevation} + \text{Friction}\). Pressure drops as fluid moves downstream.

Question 5: Pressure at Midpoint (Point A)

Principle

Calculate pressure at \(L=1000\) ft. Head loss is proportional to length.

Mini-Lesson

Hydraulic Grade Line (HGL): The HGL drops linearly for a pipe of constant diameter and roughness. We can interpolate losses based on distance.

Pedagogical Note

Intermediate points are critical. Even if the end pressure is zero, a high point in the middle could have negative pressure.

Norms

A minimum residual pressure (e.g., 20 psi) is often required at all points in a distribution system to prevent back-siphonage.

Formula(s)

Hypotheses

Linear head loss distribution (constant D and f).

Data

| Parameter | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| Length to A | 1000 | ft |

| Elevation at A | 75 | ft |

Tips

Pressure at any point x: \(P_x/\gamma = HGL_x - z_x\).

Schematic (Before Calculations)

Profile View

Calculation(s)

Step 1: Calculate Head Loss to Point A. Since head loss is linear with length, the loss at the midpoint (1000 ft) is exactly half of the total loss (2000 ft).

Step 2: Energy Balance from Pump to A. The energy at the pump equals the energy remaining at point A plus the energy lost to friction up to that point.

Since the pipe diameter is constant, the velocity is constant (\(v_1 = v_A\)). Therefore, the velocity head terms on both sides cancel out, simplifying the equation.

Step 3: Solve for Pressure Head at A (\(P_A/\gamma\)). We rearrange the equation to find the unknown pressure head at A.

We know \(P_1/\gamma = 172.58\) ft (from Q4), \(z_1=0\), \(z_A=75\), and \(h_{f,A}=11.45\).

The hydraulic grade line is at 86.13 ft above point A.

Step 4: Convert Head to PSI. Finally, convert the pressure head back to pressure units.

The pressure at the midpoint is 37.3 psi.

Schematic (After Calculations)

Hydraulic Grade Line Visualization.

HGL Drop at Point A

Analysis

The pressure has dropped from ~75 psi at the pump to ~37 psi at the midpoint. This is due to both elevation gain (75 ft) and friction (11.45 ft).

Cautionary Points

If the pipe elevation profile had a high point (peak), pressure could drop below atmospheric (vacuum), potentially causing cavitation or siphon issues. Always check high points.

Key Takeaways

- Pressure must be calculated at specific points to ensure pipe ratings are respected.

- Pressure = HGL - Elevation.

Did You Know?

Pipeline profiles often have air release valves at high points to prevent air locking, which occurs when pressure drops.

FAQ

Common questions:

Final Result

Your Turn

If Point A elevation was 100 ft instead of 75 ft, calculate the new pressure (psi).

Memo Card

Q5 Summary: Intermediate pressure checks are vital for pipeline safety.

Interactive Tool: Pipeline Designer

Explore how Pipe Diameter and Flow Rate affect Head Loss and Pump Pressure required.

Design Parameters

System Performance

Final Quiz: Test Your Knowledge

1. If the pipe diameter is doubled while maintaining the same flow rate, what happens to the velocity?

2. Which of the following contributes to the value of the Reynolds number?

3. What does the Hydraulic Grade Line (HGL) represent?

Glossary

- Head Loss (\(h_L\))

- The reduction in total head (sum of elevation, velocity, and pressure heads) of the fluid as it moves through a fluid system.

- Hydraulic Grade Line (HGL)

- A graphical representation of the potential energy of the fluid (Pressure Head + Elevation Head).

- Reynolds Number (\(Re\))

- A dimensionless quantity used to predict flow patterns in different fluid flow situations (Laminar vs Turbulent).

0 Comments