Pollutant Propagation in Pressurized Networks

Context: Environmental Hydraulics and Water Quality Monitoring.

In municipal water distribution systems, tracking the propagation of substances (chlorine, contaminants, or tracers) is critical for public safety. This exercise focuses on the AdvectionTransport of a substance by bulk motion of the fluid. and dilution of a pollutant at a pipe junction. We will analyze how a contaminant introduced in a secondary line mixes with the main flow and calculate its travel time downstream using US Customary Units.

Pedagogical Note: This exercise links hydraulic continuity (flow rates) with mass balance equations. It is essential for understanding how contaminants disperse in civil engineering infrastructure.

Learning Objectives

- Apply the Law of Conservation of Mass to fluid flow (Continuity Equation).

- Calculate the resulting concentration of a mixture using Mass Balance.

- Determine flow velocity and travel time in a pressurized pipe.

- Verify the flow regime using the Reynolds Number.

Study Data

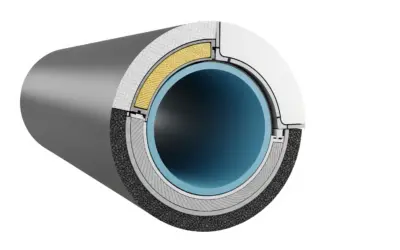

A secondary pipe (Pipe B) carrying industrial runoff containing a tracer pollutant merges into a main water supply line (Pipe A) carrying clean water. The two streams mix instantly at the junction and flow into a common output pipe (Pipe C). We need to determine the characteristics of the flow in Pipe C.

Technical Sheet / Data

| Pipe / Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Pipe A (Main) - Flow Rate | \(Q_{\text{A}} = 20 \, \text{cfs}\) (ft³/s) |

| Pipe A - Pollutant Concentration | \(C_{\text{A}} = 0 \, \text{mg/L}\) |

| Pipe B (Runoff) - Flow Rate | \(Q_{\text{B}} = 4 \, \text{cfs}\) (ft³/s) |

| Pipe B - Pollutant Concentration | \(C_{\text{B}} = 600 \, \text{mg/L}\) |

| Pipe C (Output) - Diameter | \(D_{\text{C}} = 2.5 \, \text{ft}\) (30 inches) |

| Pipe C - Length | \(L_{\text{C}} = 8000 \, \text{ft}\) |

| Kinematic Viscosity (Water @ 68°F) | \(\nu = 1.08 \times 10^{-5} \, \text{ft}^2/\text{s}\) |

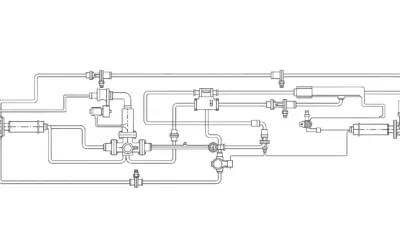

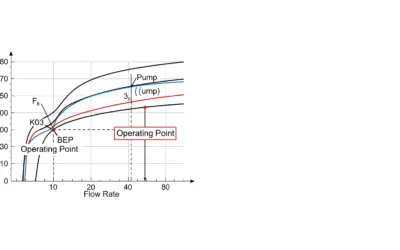

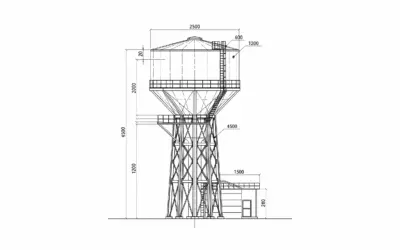

System Diagram: Junction Mixing

Questions to Address

- Calculate the total flow rate in Pipe C (\(Q_{\text{C}}\)).

- Calculate the resulting pollutant concentration in Pipe C (\(C_{\text{C}}\)).

- Calculate the flow velocity in Pipe C (\(v_{\text{C}}\)).

- Determine the Reynolds Number (\(\text{Re}\)) and the flow regime.

- Calculate the travel time (\(t\)) for the pollutant to traverse the length of Pipe C.

Theoretical Basics

Before solving, let's review the fundamental principles of fluid mechanics used in network analysis.

1. Continuity Equation (Conservation of Mass)

For an incompressible fluid (like water) at a junction, the sum of inflows equals the sum of outflows.

Flow Continuity

2. Mass Balance for Constituents

Assuming complete mixing, the mass flux of the pollutant is conserved. Mass flux is the product of Flow Rate and Concentration.

Mass Balance

3. Flow Velocity & Reynolds Number

Velocity is derived from flow rate and cross-sectional area. The Reynolds number predicts if flow is laminar or turbulent.

Velocity & Reynolds

Where:

- \(A = \pi \cdot D^2 / 4\) is the cross-sectional area.

- \(\nu\) is the kinematic viscosity (\(\approx 1.08 \times 10^{-5} \, \text{ft}^2/\text{s}\)).

- If \(\text{Re} > 4000\), flow is turbulent.

Solution: Pollutant Propagation in Pressurized Networks

Question 1: Total Flow Rate in Pipe C

Principle

We apply the Continuity Equation at the junction. Since water is incompressible, the volumetric flow rate entering the junction must equal the flow rate leaving it. In simple terms: what comes in must go out.

Key Concept

Continuity of Flow: In a steady state system, mass cannot be created or destroyed at a node. \(\sum Q_{\text{in}} = \sum Q_{\text{out}}\).

Pedagogical Note

This is the simplest form of mass balance because the fluid density is constant. If we were dealing with gases, we would need to account for density changes.

Standards

AWWA M31 (Distribution System Requirements) assumes steady-state flow for basic network sizing and modeling.

Formula(s)

Formulas Used

Sum of Flows

Assumptions

To apply this law, we make the following assumptions:

- Steady-state flow (no changes over time).

- Incompressible fluid (constant density).

- No leakage at the junction.

Data

| Parameter | Symbol | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flow A (Clean) | \(Q_{\text{A}}\) | 20 | cfs |

| Flow B (Polluted) | \(Q_{\text{B}}\) | 4 | cfs |

Tips

Always check that your units match before adding. Here, both are in cubic feet per second (cfs), so direct addition is valid.

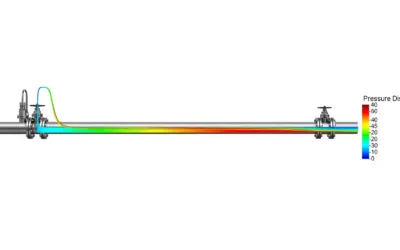

Flow Convergence

Calculations

Conversion(s)

While we work in cfs, it's useful to know the equivalent in Gallons Per Minute (GPM), common in US pump specs:

This conversion helps visualize the scale of the flow in industrial terms.

Intermediate Calculation

Checking the magnitude of the main flow:

This confirms we are dealing with a major supply line, not a small residential pipe.

Main Calculation

We substitute the variables with the known values from the Data table:

Step 1: Identify Inflows

Step 2: Add magnitudes

This sum represents the total volume of water moving into Pipe C every second.

Diagram (After Calculations)

(Visualizing the combined flow magnitude)

Reflections

The flow rate has increased by exactly 4 cfs. This represents a 20% increase over the original main flow (\(4/20 = 0.2\)).

Watch Out / Common Pitfalls

Do not confuse velocity (ft/s) with flow rate (ft³/s). You cannot add velocities directly (\(v_{\text{C}} \neq v_{\text{A}} + v_{\text{B}}\)). Only volumetric flow rates are additive.

Key Takeaways

Essential points to memorize:

- Mass is conserved at a node.

- For incompressible fluids, \(Q_{\text{in}} = Q_{\text{out}}\).

Did you know?

In the US, large scale water flow is often measured in MGD (Million Gallons per Day). 24 cfs is approximately 15.5 MGD.

FAQ

What if the pipes have different diameters?

The Continuity Equation (\(Q_{\text{total}} = \sum Q_i\)) holds true regardless of diameter changes. Diameter affects velocity, not the volumetric balance.

Your Turn

If \(Q_{\text{A}}\) increases to 30 cfs, what is the new \(Q_{\text{C}}\)?

📝 Memo

Flow addition is linear: \(Q_{\text{total}} = Q_1 + Q_2 + ...\).

Question 2: Pollutant Concentration in Pipe C

Principle

We use the Mass Balance equation for the solute. The total mass of pollutant entering the junction per second must equal the mass leaving per second.

Key Concept

Dilution: Mixing a high concentration stream with a larger zero-concentration stream significantly lowers the final concentration.

Pedagogical Note

Think of this as a "weighted average" calculation, where the "weights" are the flow rates of each pipe.

Standards

NPDES (National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System) permits often require such mixing zone calculations to ensure downstream compliance with EPA limits.

Formula(s)

Formulas Used

Concentration Mixture

Assumptions

Key assumptions for this calculation:

- Instantaneous and complete mixing at the node (ideal CSTR model).

- Conservative pollutant (no chemical decay or reaction).

Data

| Param | Value |

|---|---|

| \(C_{\text{A}}\) | 0 mg/L (Clean) |

| \(C_{\text{B}}\) | 600 mg/L (Pollutant) |

Tips

Since Pipe A has clean water, the \(Q_{\text{A}} C_{\text{A}}\) term becomes zero. This simplifies the math significantly!

Mixing Process

Calculations

Conversion(s)

Concentration is given in mg/L. No conversion is needed for the mixing ratio itself, as long as units are consistent across terms.

Unit Check

The flow units (cfs) cancel out, leaving the result in mg/L.

Intermediate Calculation

Let's calculate the "Mass Flux" (Load) for each pipe individually before summing them:

Load from Pipe A (Clean)

Load from Pipe B (Pollutant)

We now have the total load entering the junction: \(0 + 2400 = 2400\). This represents the total amount of pollutant mass per time.

Main Calculation

Now we divide the Total Load by the Total Flow (\(Q_{\text{C}}\)) calculated in Question 1:

The math simplifies perfectly to 100.

Diagram (After Calculations)

Resulting Mix Color

Reflections

The concentration dropped from 600 to 100. This is a 6x dilution factor. This occurs because the clean water flow (20 cfs) is 5 times larger than the polluted flow (4 cfs), resulting in a 1 part polluted to 5 parts clean ratio (1:6 total ratio).

Watch Out / Common Pitfalls

Don't just average 600 and 0 to get 300! An unweighted average ignores the fact that there is much more clean water than polluted water.

Key Takeaways

Essential points to memorize:

- \(C_{\text{mix}} = \sum(Q_i C_i) / \sum Q_i\)

- More clean water = Lower final concentration.

Did you know?

1 mg/L is equivalent to 1 PPM (Part Per Million) in water density, because 1 Liter of water weighs approximately 1 million milligrams (1000g).

FAQ

Does temperature affect this calculation?

Only slightly by changing water density, but for standard engineering calculations, we ignore thermal expansion effects on concentration unless the temperature difference is extreme.

Your Turn

If \(C_{\text{B}}\) was only 300 mg/L, what would be \(C_{\text{C}}\)?

📝 Memo

Dilution is proportional to flow ratios.

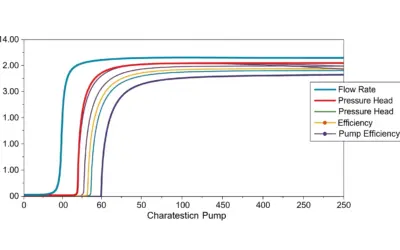

Question 3: Flow Velocity in Pipe C

Principle

Velocity represents the speed of the fluid "plug" moving through the pipe. It relates the volumetric flow rate to the pipe's physical cross-sectional area. A smaller pipe for the same flow results in higher velocity.

Key Concept

Velocity Relationship: \(Q = v \times A\). Flow Rate = Area × Speed.

Pedagogical Note

Velocity is a crucial parameter for calculating travel time (Question 5) and for checking if shear stress is sufficient to clean the pipe.

Standards

Typical municipal water main velocities are kept between 2 and 5 ft/s. Velocities above 8-10 ft/s can cause excessive head loss and water hammer issues.

Formula(s)

Formulas Used

Velocity Formula

Area Formula (Circle)

Assumptions

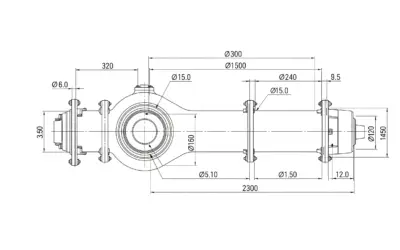

We assume:

- The pipe is flowing full (pressurized).

- The cross-section is perfectly circular.

Data

| Param | Value |

|---|---|

| \(Q_{\text{C}}\) | 24 cfs |

| \(D_{\text{C}}\) | 2.5 ft |

Tips

Remember that area scales with the square of the diameter. Doubling the diameter quadruples the area.

Pipe Cross Section

Calculations

Conversion(s)

The diameter is given in feet (2.5 ft). If it were in inches (30 inches), we would divide by 12:

Inches to Feet

We use feet to remain consistent with cfs (cubic feet per second).

Intermediate Calculation

We cannot divide Flow by Diameter directly. We need the Area (A) in square feet first.

Step 1: Radius Calculation

Step 2: Area Calculation

This 4.9087 ft² is the effective cross-sectional area available for flow.

Main Calculation

Now we divide the Flow Rate (\(Q_{\text{C}}\)) by the calculated Area (\(A\)):

Rounding to two decimal places gives us 4.89 ft/s.

Diagram (After Calculations)

(Velocity Vector)

Reflections

The calculated velocity is ~4.89 ft/s. This falls perfectly within the acceptable engineering range (2-5 ft/s). It is fast enough to prevent sediment deposition but slow enough to avoid excessive friction losses.

Watch Out / Common Pitfalls

Common error: Using Diameter in the formula \(\pi r^2\). Always use radius (\(D/2\)) or the alternate formula \(A = \frac{\pi D^2}{4}\).

Key Takeaways

Essential points to memorize:

- \(v = Q/A\).

- Consistent units (ft, cfs) prevent errors.

Did you know?

High velocities (>10 ft/s) can cause "water hammer" (destructive pressure surges) if a valve is closed suddenly, potentially bursting pipes.

FAQ

Is velocity uniform across the pipe?

In turbulent flow, the velocity profile is relatively flat (uniform), meaning the average velocity is close to the max velocity. However, theoretically, it is zero at the very walls due to the "no-slip condition".

Your Turn

If diameter was decreased to 2.0 ft, would velocity go up or down?

(It would go UP, because Area decreases while Flow stays constant)

📝 Memo

Smaller pipe = Higher speed (for same flow).

Question 4: Reynolds Number & Regime

Principle

The Reynolds Number (Re) is a dimensionless quantity used to predict flow patterns. It represents the ratio of inertial forces (momentum) to viscous forces (friction/stickiness).

Key Concept

Turbulence: High Re (>4000) indicates chaotic, mixing flow. Low Re (<2000) indicates laminar, smooth flow. Between 2000 and 4000 is transitional.

Pedagogical Note

We need to know the regime to confirm if mixing is efficient. Laminar flow does not mix lateral pollutants well; turbulent flow mixes them excellent.

Standards

The Moody Chart uses the Reynolds Number to determine the friction factor for head loss calculations in pipe networks.

Formula(s)

Formulas Used

Reynolds Number

Assumptions

Standard water properties:

- Temperature @ 68°F (determines viscosity).

- Newtonian fluid.

Data

| Param | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| Velocity \(v\) | 4.89 | ft/s |

| Diameter \(D\) | 2.5 | ft |

| Viscosity \(\nu\) | \(1.08 \times 10^{-5}\) | ft²/s |

Tips

Re has NO units. If your units don't cancel out, check your inputs (e.g., ensure viscosity is kinematic, not dynamic).

Viscosity vs Inertia

Calculations

Conversion(s)

Ensure kinematic viscosity is in ft²/s. Sometimes it is given in centistokes, which would require conversion.

Unit Check

The units cancel out perfectly.

Intermediate Calculation

Let's calculate the numerator (the inertial term) first:

This value represents momentum diffusivity potential.

Main Calculation

Now divide the inertial term by the kinematic viscosity \(\nu\):

The result is over 1.1 million.

Diagram (After Calculations)

Flow Regime Visualization

Reflections

Since \(\text{Re} \approx 1.13 \times 10^6\), which is much greater than 4000, the flow is Fully Turbulent. This guarantees that the pollutant will mix efficiently across the pipe's cross-section.

Watch Out / Common Pitfalls

Scientific notation errors are common here. Dividing by a negative exponent (\(10^{-5}\)) results in a huge number. Watch your calculator inputs.

Key Takeaways

Essential points to memorize:

- Re > 4000 = Turbulent.

- Re < 2000 = Laminar.

Did you know?

Osborne Reynolds introduced this number in 1883 by injecting dye into water pipes to visualize the transition from straight streamlines to chaotic eddies.

FAQ

Is Re usually this high?

Yes, for water transport in large municipal pipes (2.5 ft diameter), Re is almost always very high (turbulent). Laminar flow is mostly seen in tiny capillaries or very viscous fluids like oil.

Your Turn

If viscosity increased (e.g., colder water), would Re go up or down?

(It would go DOWN, because viscosity is in the denominator)

📝 Memo

Water mains = Turbulent flow.

Question 5: Travel Time Downstream

Principle

The Travel Time (or detention time) is calculated using simple kinematics. It represents how long the "plug" of pollutant takes to travel the length \(L\) of the pipe.

Key Concept

Advection Time: Time = Distance / Speed.

Pedagogical Note

This metric is critical for public safety. It tells operators how much time they have to shut down a valve or warn downstream users in case of a contamination event.

Standards

Emergency Response Plans (ERPs) for water utilities often use this method to calculate "Time to Shutdown" or "Time to Customer".

Formula(s)

Formulas Used

Time Formula

Assumptions

We assume:

- Plug Flow: The pollutant moves as a distinct block without longitudinal dispersion (spreading out ahead).

- Uniform velocity along the entire length.

Data

| Param | Value |

|---|---|

| Length \(L\) | 8000 ft |

| Velocity \(v\) | 4.89 ft/s |

Tips

The result will initially be in seconds. Convert it to minutes for a human-readable answer.

Path Animation

Calculations

Conversion(s)

We will convert seconds to minutes at the end using the standard factor:

Time Conversion

Intermediate Calculation

Just to visualize the distance, let's see how long 8000 ft is in miles:

The pollutant has to travel about 1.5 miles.

Main Calculation

Dividing the length by the velocity:

Now convert to minutes by dividing by 60:

Diagram (After Calculations)

Result

Reflections

The operators have less than half an hour (27 mins) to react if a spill occurs at point B before it reaches the end of Pipe C. This implies automated sensors might be necessary, as manual intervention might be too slow.

Watch Out / Common Pitfalls

Don't mix miles and feet. Keep everything in feet for the calculation, then convert at the end if asked.

Key Takeaways

Essential points to memorize:

- Time = L / v.

- Always convert to meaningful units (min vs sec) for reporting.

Did you know?

In reality, tracers disperse longitudinally. The "leading edge" of the pollutant will arrive slightly faster than the average time calculated here due to the velocity profile center moving faster than the average.

FAQ

What is "Plug Flow"?

Plug flow is an ideal model where fluid moves like a solid piston or "plug", with no mixing along the length. In reality, some dispersion occurs, but for turbulent flow, plug flow is a good approximation for timing.

Your Turn

If length was 4000 ft (half distance), what is the time?

📝 Memo

Distance / Speed = Time.

Exercise Summary Diagram

This diagram summarizes all calculated values, final states, and system configuration.

📝 Grand Memo: What to absolutely remember

Here is the summary of key methodological and physical points covered in this exercise:

-

🔑

Key Point 1: Dilution Logic

The final concentration is a flow-weighted average. A small polluted stream mixing with a large clean stream results in high dilution. -

📐

Key Point 2: Mass Balance Formula

Remember: \(Q_{\text{out}} C_{\text{out}} = \sum (Q_{\text{in}} C_{\text{in}})\). This applies to temperature mixing as well! -

⚠️

Key Point 3: Units Matter

Ensure flow rates match (cfs) and area calculations use Diameter (ft), not inches. -

💡

Key Point 4: Turbulence

High Reynolds numbers (>4000) indicate turbulent flow, which promotes good mixing of the pollutant.

🎛️ Interactive Simulator: Dilution Effect (US Units)

Adjust the flow rate of the clean water (Pipe A) and the concentration of the pollutant (Pipe B) to see the effect on the final concentration in Pipe C.

Parameters

📝 Final Quiz: Test your knowledge

1. If the flow rate of the clean water (Pipe A) doubles, what happens to the pollutant concentration in Pipe C?

2. What physical principle states that \(\sum Q_{\text{in}} = \sum Q_{\text{out}}\)?

📚 Glossary

- Advection

- The transport of a substance or quantity by bulk motion of a fluid.

- Mass Flux

- The rate at which mass passes through a cross-section per unit time (Mass/Time).

- Continuity

- The principle that matter cannot be created or destroyed within a system; Flow In = Flow Out.

- Turbulent Flow

- Fluid motion characterized by chaotic changes in pressure and flow velocity (High Reynolds Number).

- Tracer

- A substance introduced into a fluid system to track motion or measure flow properties.

Did You Know?

Loading...

0 Comments