Optimal Control Valve Sizing & Placement

Context: Industrial Water Distribution System

In pressurized hydraulic networks, the placement of a Control ValveA valve used to control fluid flow by varying the size of the flow passage. is critical not only for flow regulation but also to prevent mechanical damage. A major risk in such systems is CavitationFormation of vapor bubbles in a liquid caused by rapid changes in pressure., which occurs when the static pressure drops below the fluid's vapor pressure.

This exercise focuses on a gravity-fed water line connecting a high-elevation Reservoir A to a lower discharge point B. Your goal is to determine the correct valve size (\(C_v\)) and decide whether to place the valve upstream (near the reservoir) or downstream (near the discharge) to avoid cavitation.

Instructor's Note: This problem uses US Customary units (gpm, ft, psi) as per standard American engineering practice (AWWA/ASME). Pay close attention to unit conversions between Head (ft) and Pressure (psi).

Learning Objectives

- Calculate friction head loss using the Hazen-Williams equation.

- Determine the required Valve Flow Coefficient (\(C_v\)).

- Calculate the Cavitation Index (\(\sigma\)) to determine optimal valve placement.

Problem Data

A 12-inch diameter steel pipe connects Reservoir A to Discharge B. We need to regulate the flow to exactly 3,500 gpm.

Datasheet / Specifications

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Fluid | Water @ 60°F (SG = 1.0) |

| Pipe Length (\(L\)) | 4,000 ft |

| Pipe Inner Diameter (\(D\)) | 12 inches |

| Hazen-Williams C Factor | 120 (New Steel) |

| Vapor Pressure (\(P_v\)) | 0.256 psi |

| Critical Cavitation Index (\(\sigma_c\)) | 0.40 (for the selected valve) |

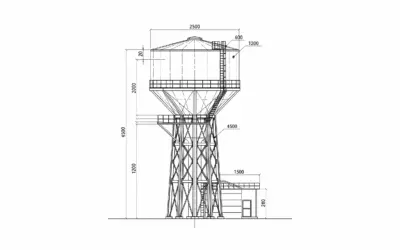

System Elevation Diagram

| Parameter Name | Symbol | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Elevation Reservoir A | \(Z_A\) | 600 | \(\text{ft}\) |

| Elevation Discharge B | \(Z_B\) | 200 | \(\text{ft}\) |

| Target Flow Rate | \(Q\) | 3,500 | \(\text{gpm}\) |

Questions

- Calculate the friction head loss (\(h_f\)) in the pipe at the target flow rate.

- Determine the required pressure drop (\(\Delta P\)) across the valve to maintain the flow.

- Calculate the required Valve Flow Coefficient (\(C_v\)).

- Calculate the Cavitation Index (\(\sigma\)) for Location 1 (Upstream/High Point).

- Calculate the Cavitation Index (\(\sigma\)) for Location 2 (Downstream/Low Point) and conclude.

Theoretical Basics

To solve this, we rely on standard hydraulic engineering formulas used in the US.

1. Hazen-Williams Equation (US Units)

Used to calculate friction head loss in water pipes.

Where:

- \(h_f\): Head loss (\(\text{ft}\))

- \(L\): Length of pipe (\(\text{ft}\))

- \(Q\): Flow rate (\(\text{gpm}\))

- \(d\): Inside diameter (\(\text{inches}\))

2. Valve Coefficient (\(C_v\))

Standard measure of valve flow capacity (US).

Where:

- \(Q\): Flow rate (\(\text{gpm}\))

- \(SG\): Specific Gravity (1.0 for water)

- \(\Delta P\): Pressure drop across valve (\(\text{psi}\))

3. Cavitation Index (\(\sigma\))

Dimensionless number used to predict cavitation potential.

Where:

- \(P_{in}\): Absolute inlet pressure (\(\text{psia}\))

- \(P_{v}\): Vapor pressure of fluid (\(\text{psia}\))

- \(\Delta P\): Pressure drop across valve (\(\text{psi}\))

Note: If \(\sigma < \sigma_c\), cavitation is likely to occur.

Solution: Optimal Control Valve Sizing & Placement

Question 1: Friction Head Loss

Principle

We must first determine how much energy is lost due to friction in the 4,000 ft pipe when water flows at 3,500 gpm. This will help us determine how much excess energy the valve needs to dissipate. We treat the pipe as a continuous element with distributed losses.

Mini-Lecture

Friction Loss: As fluid flows through a pipe, contact with the pipe walls creates shear stress, converting kinetic energy into heat. The Hazen-Williams formula is an empirical relationship specifically designed for water flows at turbulent regimes in circular pipes. It does not account for temperature changes but is highly accurate for water distribution systems.

Pedagogical Note

Although the Darcy-Weisbach equation is physically more accurate because it considers fluid viscosity and roughness height, Hazen-Williams is the industry standard for US water distribution systems because the "C-Factor" is a dimensionless constant that is easier to estimate than absolute roughness for different pipe materials.

Standards

This calculation aligns with AWWA M11 (Steel Pipe) and NFPA 13 guidelines for hydraulic calculations in fire protection and municipal water systems. The standard C-factor for new steel pipe is typically 120-140.

Formula(s)

Hazen-Williams Equation

Assumptions

To apply this law accurately, we make the following assumptions:

- The pipe diameter is constant (12 inches) throughout the 4000 ft length.

- The flow is fully developed, steady, and turbulent.

- Minor losses (fittings, bends) are considered negligible compared to the major friction loss over 4,000 ft.

Data

| Parameter | Symbol | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pipe Length | \(L\) | 4000 | \(\text{ft}\) |

| Flow Rate | \(Q\) | 3500 | \(\text{gpm}\) |

| Roughness Coefficient | \(C\) | 120 | - |

| Diameter | \(d\) | 12 | \(\text{in}\) |

Tips

To check if your result makes sense, estimate the velocity. For a 12" pipe, 10 ft/s corresponds roughly to 3500 gpm. At 10 ft/s, friction losses are significant. If you get a result like 5 ft or 5000 ft, recheck your exponents.

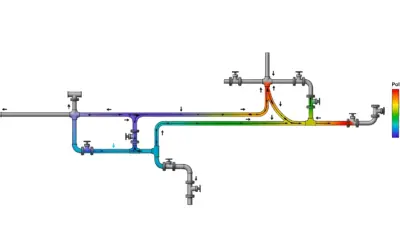

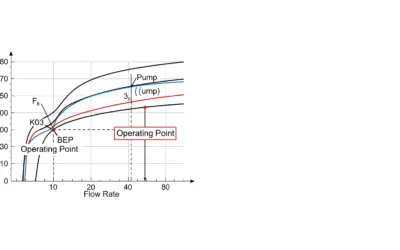

Diagram (Before Calculations)

Pipe Flow Analysis

Calculation(s)

Numerical Application

First, we compute the individual terms with exponents to simplify the fraction. This breaks down the large numbers into manageable intermediate values:

Now, we substitute these exponential values back into the numerator and denominator of the original formula to solve for head loss:

Finally, the result of 117.5 ft represents the energy dissipated per unit weight of water purely due to friction along the pipe length.

Diagram (After Calculations)

The Energy Grade Line (EGL) drops linearly by 117.5 ft over the length of the pipe due to friction.

Reflections

The result (117.5 ft) is approximately 29% of the total available static head (400 ft). This is a reasonable fraction for a transmission main. It leaves sufficient head (approx. 282 ft) to be dissipated by the control valve.

Watch Out!

Do not confuse the Diameter unit. The formula requires inches, not feet. Using \(d=1\) ft instead of \(d=12\) inches would give a wildly incorrect result because of the \(d^{4.87}\) power.

Key Takeaways

Main points to memorize:

- Head loss increases exponentially with flow rate (\(h_f \propto Q^{1.85}\)).

- A rough pipe (lower C) causes significantly more pressure loss.

- Diameter has the strongest effect on friction (\(d^{4.87}\)).

Did you know?

The exponent 1.85 was derived empirically by Hazen and Williams in the early 20th century. In the theoretical Darcy-Weisbach equation for fully turbulent flow, the exponent is exactly 2.0, but Hazen-Williams is preferred for its simplicity in waterworks.

FAQ

What if the pipe was PVC instead of Steel?

PVC is much smoother (\(C \approx 150\)). The head loss would be significantly lower, resulting in higher pressure arriving at the valve, which would then require the valve to dissipate even more energy.

Your Turn

Estimate \(h_f\) if the flow was reduced to 1000 gpm (roughly 1/3.5 of original flow)?

📝 Cheat Sheet

\(h_f \propto Q^{1.85}\). If you double the flow, you nearly quadruple the friction.

Question 2: Required Valve Pressure Drop

Principle

The valve acts as a variable resistor. It must "consume" or dissipate the excess energy in the system to limit the flow to the target rate. The required head loss across the valve is simply the Total Available Gravity Head minus the unavoidable Pipe Friction Loss.

Mini-Lecture

Bernoulli's Principle & Energy Balance: Between two points in a streamline (Reservoir A and Discharge B), the total energy is conserved. The Initial Elevation Potential Energy is converted into Friction Losses (pipe) and Minor Losses (valve). To maintain a steady state, the valve must drop exactly the amount of head required to balance the equation.

Pedagogical Note

We initially work in "Feet of Head" because gravity systems are defined by elevation. However, we must convert the final answer to PSI because valve manufacturers rate their equipment capabilities in pressure (PSI), not head.

Standards

Pressure ratings for flanges and valves often follow ASME B16.5 classes (e.g., Class 150, Class 300). Knowing the \(\Delta P\) helps select the correct pressure class to avoid component failure.

Formula(s)

Bernoulli Balance

Head to Pressure Conversion

Assumptions

To simplify the calculation, we assume:

- Kinetic energy changes ($v^2/2g$) are negligible (velocity is constant in constant diameter pipe).

- Water temperature is 60°F (Density standard), giving the conversion factor 2.31 ft/psi.

Data

| Parameter | Symbol | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Elevation A | \(Z_A\) | 600 | \(\text{ft}\) |

| Elevation B | \(Z_B\) | 200 | \(\text{ft}\) |

| Friction Loss | \(h_f\) | 117.5 | \(\text{ft}\) |

Tips

A quick mental check: The valve must drop whatever height remains. 400 ft total minus ~100 ft friction means the valve takes the remaining ~300 ft.

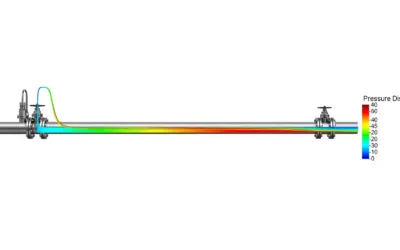

Diagram (Before Calculations)

Energy Budget Visualization

Calculation(s)

Numerical Application

First, we determine the total driving force available from gravity by finding the difference in elevation between the two reservoirs:

Next, we subtract the energy lost to pipe friction (calculated in Question 1) to find the excess head that the valve must dissipate:

Finally, we convert this head loss into pressure units (PSI) for valve selection, dividing by 2.31 (for water):

Diagram (After Calculations)

The valve effectively replaces 282.5 ft of pipe friction to balance the system energy.

Reflections

122 psi is a significant pressure drop. This suggests high energy dissipation, meaning potential noise, vibration, and a strong risk of cavitation depending on where the valve is located.

Watch Out!

Common Unit Trap: Hydraulic formulas often give results in Feet of Head. Valve sizing and cavitation checks usually require PSI. Always divide Feet by 2.31 (for water) to get PSI.

Key Takeaways

Main points to memorize:

- The valve must dissipate all head not lost to friction.

- 1 PSI = 2.31 ft of Water Head.

Did you know?

Standard household pressure is 40-60 psi. This valve is dropping twice that amount in a single device, equivalent to the pressure at 280 feet underwater.

FAQ

Why don't we just use a smaller pipe to increase friction?

We could, but control valves allow us to vary the resistance dynamically as demand changes. A fixed small pipe would only work for one specific flow rate and offers no control.

Your Turn

If friction loss was 0 ft (hypothetical), what would be the max valve \(\Delta P\)?

📝 Cheat Sheet

Total Head = Friction + Valve Drop.

Question 3: Valve Flow Coefficient (\(C_v\))

Principle

The \(C_v\) represents the valve's capacity. It is formally defined as the number of gallons per minute of water at 60°F that will flow through the valve with a 1 psi pressure drop across it. We use this coefficient to select a valve size from a manufacturer's catalog.

Mini-Lecture

Flow Coefficient (\(C_v\)): This is the universal language of valve sizing in the US (in Europe, \(K_v\) is used). It combines the flow area and the flow geometry into a single number. A larger \(C_v\) means a larger opening.

Pedagogical Note

In a real catalog, you would select a valve with a max \(C_v\) larger than the calculated value (typically \(C_{v, calculated} \approx 0.60 \times C_{v, max}\)) to ensure controllability and room for error.

Standards

Sizing equations are governed by ISA-75.01.01 (Flow Equations for Sizing Control Valves). This standard ensures consistency across different valve types.

Formula(s)

Cv Equation

Assumptions

To solve this, we assume:

- Non-choked flow (no cavitation/flashing effects affecting capacity yet).

- Standard Gravity (SG) = 1.0 for water.

Data

| Parameter | Symbol | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flow Rate | \(Q\) | 3500 | \(\text{gpm}\) |

| Pressure Drop | \(\Delta P\) | 122.3 | \(\text{psi}\) |

| Specific Gravity | SG | 1.0 | - |

Tips

Remember: Large \(\Delta P\) allows a smaller valve (smaller \(C_v\)) to pass the same flow. It's like putting your thumb over a hose; higher pressure spray requires a smaller opening.

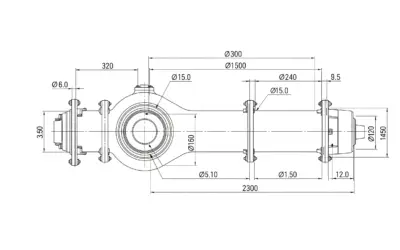

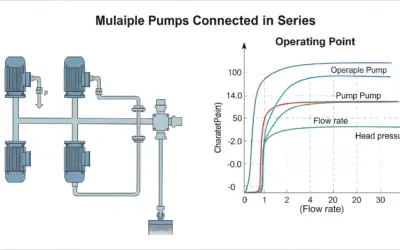

Diagram (Before Calculations)

Valve Anatomy & Cv

Calculation(s)

Numerical Application

We start with the standard Cv formula:

We substitute the known values: Flow \(Q = 3500\) gpm and Pressure Drop \(\Delta P = 122.3\) psi:

Solving the square root term first and then multiplying by the flow rate gives the required capacity:

Diagram (After Calculations)

Reflections

A \(C_v\) of 316 is relatively small for a 12" pipe system (typically a 12" valve has \(C_v > 2000\)). This implies the valve will be significantly throttled (closed down) or, more likely, a smaller valve (e.g., 6" or 8") should be installed with reducers to achieve better control resolution.

Watch Out!

Don't confuse \(C_v\) with \(K_v\). \(K_v\) is the metric equivalent (m³/h @ 1 bar). \(C_v \approx 1.156 \times K_v\).

Key Takeaways

Main points to memorize:

- Higher pressure drop \(\to\) Smaller required \(C_v\).

- The calculated \(C_v\) is the required capacity at the specific operating point.

Did you know?

The term "Trim" in a valve refers to the internal parts (plug, seat, stem) that control the flow. Changing the trim can change the \(C_v\) without changing the valve body size.

FAQ

Can I just use a 12 inch valve?

Probably not. A 12" valve might have a max Cv of 2000+. To get down to 316, it would be barely open (<10%), causing erosion and poor control. You need a smaller valve.

Your Turn

If \(\Delta P\) was 4 times larger, how would Cv change?

📝 Cheat Sheet

\(C_v\) equation is just Ohm's law for fluids: Flow = Conductance \(\times\) \(\sqrt{\text{Potential}}\).

Question 4: Cavitation Check - Location 1 (Upstream)

Principle

We verify the cavitation risk at Location 1, just downstream of Reservoir A (El. 590 ft). At this high point, there is very little static head above the valve, resulting in low inlet pressure. We compare the Cavitation Index to the critical limit.

Mini-Lecture

Cavitation: Occurs when static pressure drops below vapor pressure (\(P_v\)). The liquid boils at ambient temperature, forming bubbles. When pressure recovers downstream, these bubbles implode violently, blasting the metal surface and causing noise and damage.

Pedagogical Note

The "Sigma" (\(\sigma\)) index is our safety factor. High sigma = Safe. Low sigma = Danger. It essentially measures how much "pressure buffer" we have relative to the violence of the pressure drop.

Standards

Cavitation limits are often defined by ISA-75.23 (Considerations for Evaluating Control Valve Cavitation). A \(\sigma\) below 1.0 typically signals caution, and below 0.4 often signals severe cavitation for standard valves.

Formula(s)

Cavitation Index

Assumptions

- Valve Elevation \(\approx\) 590 ft (10 ft below water surface).

- Inlet Head \(\approx\) 10 ft (friction is negligible for this short distance).

- Atmospheric Pressure \(P_{atm} \approx 14.7\) psi.

Data

| Parameter | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| Inlet Head | 10 | \(\text{ft}\) |

| Vapor Pressure | 0.256 | \(\text{psia}\) |

| Valve Drop | 122.3 | \(\text{psi}\) |

Tips

Always convert Gauge pressure to Absolute pressure before calculating Sigma. Vapor pressure is absolute, so inlet pressure must match. \(P_{abs} = P_{gauge} + 14.7\).

Diagram (Before Calculations)

Pressure Profile (Upstream Loc 1)

Calculation(s)

Step 1: Calculate Absolute Inlet Pressure (\(P_{in}\))

First, determine the absolute pressure at the valve inlet. Since the valve is high up, there is little water above it:

This inlet pressure of 19.03 psia is dangerously low relative to the massive pressure drop required.

Step 2: Calculate Cavitation Index (\(\sigma\))

Now, calculate the Cavitation Index \(\sigma\) using the inlet pressure and pressure drop to check safety:

A result of 0.15 indicates extreme cavitation danger, far below the critical limit of 0.4.

Diagram (After Calculations)

Cavitation Damage Mechanism

Reflections

Since \(\sigma (0.15) < \sigma_c (0.40)\), Severe Cavitation will occur. Placing the valve high up effectively creates a vacuum downstream of the valve because the inlet pressure is too weak to support the massive pressure drop.

Watch Out!

Low \(\sigma\) means the valve will sound like gravel is flowing through it. It can destroy the valve trim in hours.

Key Takeaways

Main points to memorize:

- Low inlet pressure increases cavitation risk.

- Avoid placing control valves at high elevations with high pressure drops.

Did you know?

Special "Anti-Cavitation" valve trims exist, using multi-stage pressure drops (like a stack of washers) to keep pressure above vapor limit, but they are expensive.

FAQ

What is Flashing?

If the downstream pressure stays below vapor pressure, the bubbles don't implode; they stay as gas. This is "Flashing". It causes erosion but less vibration than cavitation.

Your Turn

How much inlet pressure (psia) would we need to get \(\sigma = 0.4\)? (\(P_{req} = 0.4 \times 122.3 + 0.256\))

📝 Cheat Sheet

Low Inlet P + High \(\Delta P\) = Cavitation Nightmare.

Question 5: Cavitation Check - Location 2 (Downstream)

Principle

We check Location 2, at the bottom of the hill (El. 200 ft), just before the discharge. The full weight of the water column provides "backpressure" or high inlet pressure, which helps suppress bubble formation.

Mini-Lecture

Backpressure: By increasing the absolute pressure at both inlet and outlet, we move the entire pressure profile up, staying safely away from the Vapor Pressure line (\(P_v\)). It's like submerging a boiling pot; pressure stops the boil.

Pedagogical Note

Location 2 is physically lower (400 ft lower) than Location 1. This adds static head to the inlet, raising \(P_{in}\) significantly.

Standards

Industrial best practice (ISA/EPRI) recommends locating valves at the lowest possible elevation for liquid service to maximize static head and minimize cavitation risk.

Formula(s)

Head Calculation

Assumptions

- Valve is at El. 200.

- Friction loss occurs upstream of the valve.

Data

| Parameter | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| Valve Elev | 200 | \(\text{ft}\) |

| Static Head | 400 | \(\text{ft}\) |

Tips

The \(\Delta P\) across the valve is roughly the same (assuming \(P_{out}\) adapts), but \(P_{in}\) is massive here.

Diagram (Before Calculations)

Pressure Profile (Downstream Loc 2)

Calculation(s)

Step 1: Calculate Inlet Pressure (\(P_{in}\))

First, calculate the inlet pressure at the bottom of the hill. The static head is much higher here, minus the friction losses upstream:

Note: \(P_{in}\) here essentially equals the \(\Delta P\) required + any backpressure (which is 0 here from downstream, but the absolute inlet is high).

Step 2: Calculate Cavitation Index (\(\sigma\))

Now we recalculate \(\sigma\). The Inlet Pressure term is now 137 psia instead of 19 psia, providing a massive buffer:

Diagram (After Calculations)

Safe Operation

σ = 1.12 ≫ 0.40

Reflections

Since \(\sigma (1.12) > \sigma_c (0.40)\), No Cavitation will occur. The high inlet pressure (backpressure provided by the water column) suppresses bubble formation completely.

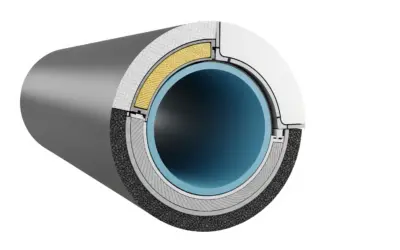

Watch Out!

Ensure the valve body rating (e.g., ANSI 150 vs 300) can handle the 122 psi static pressure (plus potential surge pressure) when the valve is closed.

Key Takeaways

Main points to memorize:

- High backpressure helps prevent cavitation.

- Always check \(\sigma\) against the valve manufacturer's critical coefficient.

Did you know?

Some valves (like Ball valves) recover pressure better than others (like Globe valves), affecting their cavitation limits. A ball valve might cavitate earlier due to high recovery factor ($F_L$).

FAQ

Is there any downside to Location 2?

The pipe between the reservoir and Location 2 is under high pressure. If it bursts, the entire reservoir drains. Location 1 would stop the leak sooner, but Location 2 is required for process control.

Your Turn

Is \(\sigma=1.12\) safe if \(\sigma_c=0.9\)?

📝 Cheat Sheet

Location, Location, Location. Downstream is safer for pressure drops.

Exercise Summary Diagram

Visual summary of Hydraulic Grade Line (HGL) and Pressure Profiles.

📝 Main Takeaway: Absolute Must-Knows

When designing control systems in pressurized networks:

-

🔑

Energy Conservation

The valve must kill all energy not used by friction. \(\Delta P_{valve} = P_{static} - P_{friction}\). -

📐

Cavitation is about Ratio

It depends on the ratio of Inlet Pressure to Pressure Drop. \(\sigma = (P_{in} - P_v) / \Delta P\). -

⚠️

Placement Matters

Always place high-drop valves in high-pressure zones (downstream/low elevation) to suppress cavitation.

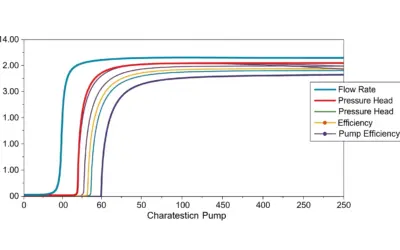

🎛️ Valve & Cavitation Simulator

Adjust the flow rate and backpressure to see if the valve cavitates.

Parameters

📝 Final Quiz: Test your knowledge

1. Why is Location 2 (Downstream) better for the valve?

2. If the flow rate (\(Q\)) doubles, what happens to friction head loss (\(h_f\))?

📚 Glossary

- Cavitation

- The formation and rapid collapse of vapor bubbles in a liquid due to low pressure, often causing damage to valves and pipes.

- Hazen-Williams C

- Roughness coefficient for pipes. Higher C means smoother pipe (less friction). Plastic = 150, Old Iron = 100.

- Head Loss (\(h_f\))

- Energy loss due to friction as fluid moves through a pipe, expressed in feet of water column.

- Cv (Flow Coefficient)

- Standard US unit for valve capacity. Defined as gpm of 60°F water with a 1 psi pressure drop.

- Static Head

- Pressure energy potential due to elevation difference (e.g., height of water in a tank).

Did you know?

Loading...

0 Comments