Centrifugal Pump Analysis: Determining the Operating Point

Context: Hydraulic Network AnalysisThe study of flow and pressure distribution in piping systems..

In industrial and civil engineering applications, selecting the correct pump for a piping system requires analyzing the interaction between the pump's performance and the system's resistance. This exercise focuses on determining the Operating Point of a centrifugal pump transferring water between two reservoirs in a pressurized system. You will use the Energy Equation (Bernoulli) and the Darcy-Weisbach (or equivalent resistance) method to find the intersection of the Pump Curve and the System Curve.

Pedagogical Note: This exercise simulates a real-world scenario faced by Hydraulic Engineers. Understanding how changes in static head or valve position affect the flow rate \(Q\) and head \(H\) is crucial for designing efficient and safe pumping stations.

Learning Objectives

- Identify the components of a system head curve: Static Head vs. Dynamic (Friction) Head.

- Calculate the Total Dynamic Head (TDH) required by the system.

- Derive the System Curve equation (\(H_{\text{sys}} = H_{\text{stat}} + K \cdot Q^2\)).

- Determine the Operating Point by finding the intersection of the System Curve and the Pump Curve.

- Analyze the effect of system changes (e.g., throttling a valve) on the operating point.

Study Data

Fluid Properties (Water @ 68°F)

| Property | Value |

|---|---|

| Density (\(\rho\)) | 62.4 \(\text{lb/ft}^3\) |

| Kinematic Viscosity (\(\nu\)) | \(1.08 \times 10^{-5}\) \(\text{ft}^2/\text{s}\) |

| Gravity (\(g\)) | 32.2 \(\text{ft/s}^2\) |

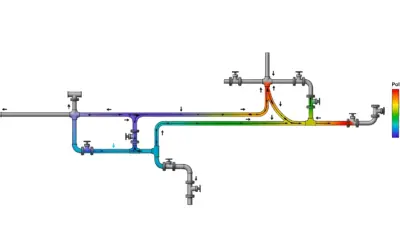

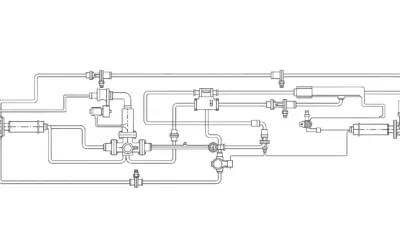

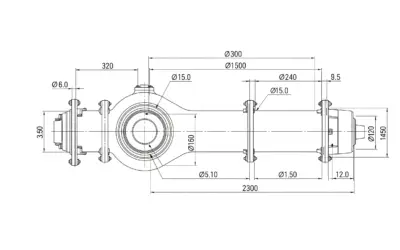

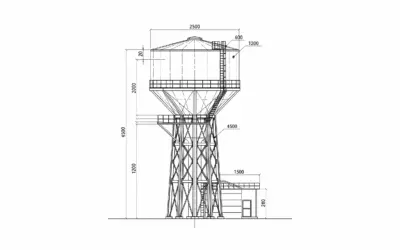

System Schematic

| Parameter | Symbol | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Elevation, Supply Tank | \(z_1\) | 20 | \(\text{ft}\) |

| Elevation, Discharge Tank | \(z_2\) | 100 | \(\text{ft}\) |

| Pump Curve Equation (approx) | \(H_{\text{pump}}(Q)\) | \(160 - 0.0002 Q^2\) | Head in \(\text{ft}\), Q in \(\text{gpm}\) |

| Approx. Resistance Coefficient | \(C_{\text{sys}}\) | 0.0003 | \(\text{ft}/\text{gpm}^2\) |

Questions to Address

- Calculate the Static Head (\(H_{\text{stat}}\)) of the system.

- Write the equation for the System Curve (\(H_{\text{sys}}\)) in terms of flow rate \(Q\).

- Solve algebraically for the Operating Point flow rate (\(Q_{\text{op}}\)).

- Calculate the Total Dynamic Head (\(H_{\text{op}}\)) at the operating point.

- Analyze the effect of partially closing the discharge valve on the operating point.

Fundamentals of Hydraulic Systems

To solve this, we rely on the conservation of energy applied to incompressible flow.

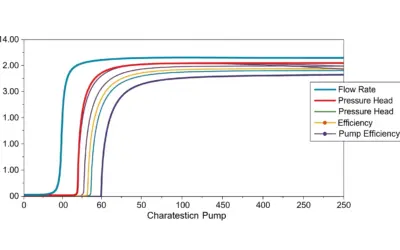

1. The System Curve

The system head required is the sum of the static lift and the dynamic losses (friction + minor losses).

\[ H_{\text{sys}} = \Delta z + h_L = (z_2 - z_1) + C_{\text{sys}} \cdot Q^2 \]

Where \(C_{\text{sys}}\) aggregates pipe friction and valve/fitting losses.

2. The Operating Point

The pump operates where the energy it provides equals the energy required by the system. This is the intersection of the Pump Curve and System Curve.

\[ H_{\text{pump}}(Q) = H_{\text{sys}}(Q) \]

Solution: Centrifugal Pump Analysis

Question 1: Calculate the Static Head (\(H_{\text{stat}}\))

Principle

Static head represents the vertical distance the pump must lift the fluid regardless of the flow rate. It corresponds to the potential energy change.

Mini-Lesson

Definition: Static Head is strictly the elevation difference between the free surface of the discharge reservoir and the supply reservoir. It is independent of the piping path or diameter.

Pedagogical Note

Even if the pipe goes up and down over hills, the static head is determined only by the start and end points (assuming the pipe remains full).

Norms

ASME B31.1 (Power Piping) defines standard practices for determining elevation heads in layouts.

Formula(s)

Hypotheses

We assume both tanks are open to the atmosphere (pressure cancels out) and velocity head in the tanks is negligible.

Data

From the problem statement:

| Parameter | Symbol | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Discharge Elevation | \(z_2\) | 100 | \(\text{ft}\) |

| Supply Elevation | \(z_1\) | 20 | \(\text{ft}\) |

Tips

Don't subtract the pump elevation! The pump elevation matters for NPSH (cavitation) but not for the total system Static Head.

Schematic (Before Calculations)

Elevation Difference Concept

Calculation(s)

Step 1: Identify Elevations and Subtract

We identify the surface elevation of the Discharge Tank (\(z_2\)) and the Supply Tank (\(z_1\)) from the data provided. Then we substitute these values into the static head formula.

Step 2: Subtract

We subtract the lower elevation from the higher elevation to find the total vertical lift required.

Key Takeaways

- The pump must produce at least 80 ft of head just to initiate flow (Shut-off Head condition).

- This value is independent of the pipe diameter or length.

Did You Know?

In closed-loop systems (like home heating), the static head is essentially zero for the pump because the water returns to the same elevation. The pump only overcomes friction.

Final Result

Your Turn

If the discharge tank level drops to 90 ft, what is the new static head?

Memo Card

Static Head Summary:

- Formula: \(\Delta z\)

- Unit: Feet (ft) or Meters (m)

- Role: Minimum energy hurdle.

Question 2: Establish the System Curve Equation

Principle

The total head required (\(H_{\text{sys}}\)) increases with the square of the flow rate due to turbulent friction losses. We combine the static head calculated in Q1 with the dynamic losses.

Mini-Lesson

Square Law: In turbulent flow (typical for water supply), friction losses (\(h_f\)) are proportional to velocity squared (\(v^2\)), and since \(Q = vA\), \(h_f \propto Q^2\).

Pedagogical Note

We often group all friction factors (pipe length, diameter, roughness) and minor losses (elbows, valves) into a single coefficient \(K\) or \(C_{\text{sys}}\).

Norms

Darcy-Weisbach is the standard method (ASME) for friction calculations, though Hazen-Williams is common in civil waterworks.

Hypotheses

We assume fully turbulent flow where the friction factor \(f\) is relatively constant, allowing us to use the simplified form \(K \cdot Q^2\).

Formula(s)

Data

Static Head: \(H_{\text{stat}} = 80\) ft.

Resistance Coefficient given: \(C_{\text{sys}} = 0.0003\) \(\text{ft}/\text{gpm}^2\).

Tips

Always ensure your units for \(Q\) (\(\text{gpm}\)) match the resistance coefficient units (\(\text{ft}/\text{gpm}^2\)). Mixing cfs and gpm is a common error.

Schematic (Before Calculations)

Total Head Composition

Calculation(s)

Step 1: Write General Form

We begin with the general equation for the System Curve, which is the sum of the Static Head and the Dynamic Friction Losses.

Step 2: Substitute Knowns

Now we replace the symbols with the values we have found: \(H_{\text{stat}}=80\) ft from Question 1 and \(C_{\text{sys}}=0.0003\) \(\text{ft}/\text{gpm}^2\) from the data table. This gives us the final equation describing the system's demand at any flow \(Q\).

Schematic (After Calculations)

System Curve Shape

Analysis

The curve starts at \(H=80\) (y-intercept). This confirms that at zero flow, the pressure is just the static head. As flow increases, the required head rises exponentially.

Cautionary Points

This parabolic curve assumes turbulent flow. In laminar flow (very viscous fluids like oil), head is proportional to \(Q\), not \(Q^2\).

Key Takeaways

- The System Curve describes the energy consumer (the pipe network).

- Steeper curves indicate high resistance (small pipes, closed valves).

Did You Know?

Over time, as pipes age and corrode, the roughness increases, causing the coefficient \(C_{\text{sys}}\) to increase and the curve to become steeper.

Final Result

Your Turn

Calculate the required system head if the flow rate is 100 gpm.

Memo Card

System Curve Summary:

- Formula: \(H_{\text{sys}} = H_{\text{stat}} + K \cdot Q^2\)

- Shape: Parabola starting at \(H_{\text{stat}}\).

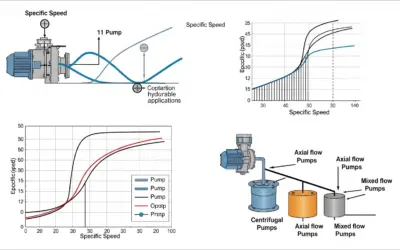

Question 3: Determine the Operating Point Flow Rate (\(Q_{\text{op}}\))

Principle

The stable operating point occurs where the pump's energy supply matches the system's energy demand. We set the Pump Equation equal to the System Equation.

Mini-Lesson

Operating Intersection: Just like Supply and Demand in economics, the operating point is the unique flow rate where the pump "can do" exactly what the system "requires".

Pedagogical Note

You can solve this graphically (plotting both curves) or algebraically. We will use the algebraic method for precision.

Norms

Hydraulic Institute (HI) Standards recommend operating within 70-120% of the Best Efficiency Point (BEP) for pump longevity.

Hypotheses

We assume the pump is running at a constant speed (no VFD) and the system conditions are steady.

Formula(s)

Equations

Tips

Group the \(Q^2\) terms on one side and the constants on the other side before solving.

Schematic (Before Calculations)

Balance of Energy

Calculation(s)

Step 1: Set Equations Equal

We start by equating the Pump Head equation to the System Head equation to find the intersection point.

Step 2: Group Terms

Next, we move all terms containing \(Q^2\) to the right side and all constant terms to the left side. Notice how the sign of \(0.0002 Q^2\) changes from negative to positive as it moves across the equals sign.

Step 3: Simplify

We perform the arithmetic: \(160 - 80 = 80\) and \(0.0003 + 0.0002 = 0.0005\).

Step 4: Solve for \(Q^2\)

We isolate \(Q^2\) by dividing both sides by the coefficient \(0.0005\). Dividing by a decimal is equivalent to multiplying by its reciprocal.

Step 5: Solve for \(Q\)

Finally, we take the square root of both sides to find the flow rate \(Q\). We only consider the positive root since flow cannot be negative in this context.

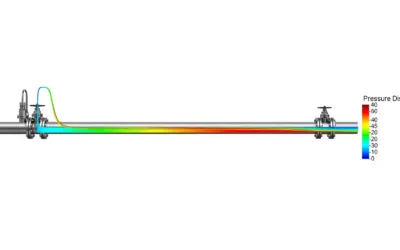

Schematic (After Calculations)

Resulting Flow Rate

Analysis

The flow rate of 400 gpm is the natural equilibrium. If flow were higher, the system would require more head than the pump can give, slowing the flow down. If flow were lower, the pump would provide excess head, accelerating the flow.

Cautionary Points

Always check if the calculated flow is within the pump's allowable operating range. Operating too far left leads to cavitation/recirculation; too far right leads to motor overload.

Key Takeaways

- Algebraic solution finds the exact intersection.

- The intersection moves if either the pump curve (speed change) or system curve (valve change) shifts.

Did You Know?

Pumps are rarely perfectly matched to the system. Engineers typically select a slightly larger pump and trim the impeller or use a VFD to hit the exact point.

Final Result

Your Turn

If the pump equation was \(H_{\text{pump}} = 160 - 0.0001 Q^2\) and the system remained the same, calculate \(Q^2\) (Squared Flow).

Memo Card

Calculation Summary:

- Step 1: Equate \(H_{\text{sys}} = H_{\text{pump}}\).

- Step 2: Solve for \(Q\).

Question 4: Calculate the Head at the Operating Point (\(H_{\text{op}}\))

Principle

Now that we have the flow rate, we can calculate the head produced by the pump (or required by the system) at this specific rate. Both equations should yield the same result.

Mini-Lesson

Total Dynamic Head (TDH): The total energy per unit weight added to the fluid. Ideally, we check both equations to verify our algebra.

Pedagogical Note

Verifying using both equations is a "sanity check". If they differ, you made a mistake calculating \(Q\).

Norms

ANSI/HI 1.6 testing standards dictate that the factory-tested head must be within a specific tolerance of the published curve at the rated flow.

Hypotheses

We assume the fluid properties (density, viscosity) match the conditions for which the pump curve was derived.

Formula(s)

Data

Operating Flow Rate \(Q = 400\) gpm (from Question 3).

Tips

Use the simpler equation (often the System Curve) for the first calculation, then the Pump Curve for verification.

Calculation(s)

Step 1: Calculate System Required Head

We insert the operating flow \(Q=400\) back into the System Curve equation to find the head required by the piping.

Step 2: Verify with Pump Available Head

Now, we perform the same check using the Pump Curve equation to calculate the head provided by the pump at that flow.

Result: Both calculations yield 128 ft, confirming our operating point is correct.

Schematic (After Calculations)

Final Operating Point Graph

Analysis

The operating head is 128 ft. This means the pump is boosting the fluid pressure by an equivalent of 128 feet of water column to overcome both the 80 ft elevation and the friction losses.

Cautionary Points

Ensure this discharge pressure does not exceed the Maximum Allowable Working Pressure (MAWP) of the downstream pipes or valves.

Key Takeaways

- Total Head is a combination of Static Lift and Friction Loss.

- At the operating point, \(H_{\text{pump}} = H_{\text{sys}}\).

Did You Know?

"Head" is used instead of "Pressure" (psi) because a pump generates the same head regardless of fluid density, whereas the pressure in psi changes with fluid weight.

Final Result

Memo Card

Verification Tip: Always calculate H using both formulas. If they don't match, there is an algebra error in \(Q\).

Your Turn

Calculate the pressure in psi corresponding to 128 ft of head (SG=1.0). Hint: psi = Head / 2.31.

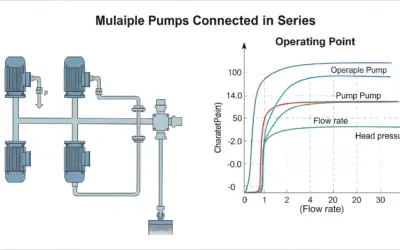

Question 5: Analysis of Throttling

Principle

Throttling means partially closing the discharge valve. This adds resistance to the flow, effectively increasing the value of \(C_{\text{sys}}\).

Mini-Lesson

Valve Coefficient (Kv/Cv): Closing a valve increases the localized pressure drop. In our equation \(H_{\text{sys}} = H_{\text{stat}} + C_{\text{sys}} \cdot Q^2\), the term \(C_{\text{sys}}\) increases.

Pedagogical Note

Think of throttling like squeezing a garden hose. The pressure behind your thumb goes up (Pump Head increases), but the amount of water coming out goes down (Flow decreases).

Norms

ISA-75.01 standards govern flow equations for sizing control valves and predicting pressure drop.

Hypotheses

We assume the pump speed remains constant and the static head does not change.

Formula(s)

Where \( C_{\text{sys}}' > C_{\text{sys}} \).

Data

Qualitative analysis: The resistance coefficient \(C_{\text{sys}}\) increases (e.g., from 0.0003 to 0.0005).

Tips

Throttling moves the operating point along the Pump Curve, not the System Curve. The System Curve itself changes shape.

Analysis

If we close the valve slightly:

Conclusion: Throttling reduces the flow rate but increases the pressure head developed by the pump. This is inefficient because energy is wasted across the valve (friction heat).

Schematic (After Calculations)

Effect of Throttling on Curves

Cautionary Points

Avoid excessive throttling for long periods, as it forces the pump to operate far to the left of its curve, potentially causing vibration, overheating, or bearing failure.

Key Takeaways

- Throttling increases system resistance.

- It reduces flow but increases pump head.

- It is an energy-inefficient method of flow control.

Did You Know?

Using a Variable Frequency Drive (VFD) to slow the pump down is a much more energy-efficient way to reduce flow than throttling a valve, as it reduces the energy consumption significantly.

Final Result

Your Turn

Does throttling change the Static Head?

Memo Card

Control Summary:

- Valve: Changes System Curve Slope.

- VFD: Changes Pump Curve Height.

Interactive Tool: Pump vs. System Simulator

Use the sliders to change the Static Head (elevation difference) and the Valve Friction (system resistance) to see how the operating point shifts.

System Parameters

Operating Point Results

Final Quiz: Test Your Knowledge

1. What happens to the System Curve if the pipe diameter is decreased (assuming same length)?

2. Which method is most energy-efficient for reducing the flow rate in a pumping system?

3. If the Static Head (\(H_{\text{stat}}\)) is greater than the pump's Shut-off Head (\(H_0\)), what happens?

Glossary

- Static Head

- The vertical distance in feet from the supply surface level to the discharge surface level.

- Friction Head

- The energy loss due to the fluid rubbing against pipe walls and fittings.

- Operating Point

- The specific flow rate and head where the system curve intersects the pump curve.

- Shut-off Head

- The maximum head a pump can generate at zero flow rate.

0 Comments