Cavitation in a Venturi System

Context: Hydraulic FundamentalsThe study of fluid mechanics principles as applied to water and other liquids in motion or at rest..

This exercise explores the critical phenomenon of cavitationThe formation and rapid collapse of vapor bubbles in a liquid when the local pressure drops below the vapor pressure.. We will use Bernoulli's EquationA statement of energy conservation for a flowing fluid, relating pressure, velocity, and elevation. to predict when the pressure in a system drops to the fluid's vapor pressureThe pressure at which a liquid will boil (turn to vapor) at a given temperature., leading to cavitation. We will analyze a Venturi pipe system drawing water from a reservoir to determine the maximum flow rate before damaging cavitation bubbles begin to form.

Pedagogical Note: This exercise will teach you to apply the energy equation (Bernoulli) in a practical context to identify the operational limits of a fluid system before cavitation occurs. It emphasizes the importance of using consistent units (US customary units) and understanding absolute vs. gage pressure.

Learning Objectives

- Understand the physical concept and conditions for cavitation.

- Apply Bernoulli's equation using US customary units (ft, psi, psf, ft/s).

- Use the continuity equation (\(Q=AV\)) to relate fluid velocity and pipe area.

- Determine the maximum flow rate in a constricted pipe before cavitation begins.

- Differentiate between absolute and gage pressure in hydraulic calculations.

Study Data

System Specifications

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Fluid | Water |

| System Type | Venturi Pipe from Reservoir |

| Atmospheric Pressure (\(p_{atm}\)) | 14.7 psi |

| Gravity (\(g\)) | 32.2 ft/s² |

System Schematic

| Parameter | Symbol | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reservoir Elevation | \(z_1\) | 20 | ft |

| Throat Elevation | \(z_2\) | 0 | ft (Datum) |

| Inlet Pipe Diameter | \(D_1\) | 6 | in |

| Throat Diameter | \(D_2\) | 3 | in |

| Water Temperature | \(T\) | 70 | °F |

| Vapor Pressure (at 70°F) | \(p_v\) | 0.363 | psi (absolute) |

| Specific Weight (at 70°F) | \(\gamma\) | 62.3 | lb/ft³ |

Questions to Address

- Convert all parameters (diameters, pressures) to consistent base units in the US customary system (feet, pounds per square foot (psf)). Calculate the areas \(A_1\) and \(A_2\).

- State the Continuity Equation (relating \(V_1\) and \(V_2\)) and the full Bernoulli's equation (in head form) that will be used.

- Apply Bernoulli's equation between the reservoir surface (Point 1) and the throat (Point 2) to find the throat velocity (\(V_2\)) at the exact moment cavitation begins.

- Using the throat velocity (\(V_2\)), calculate the volumetric flow rate (\(Q\)) in cubic feet per second (cfs). Then, convert this flow rate to gallons per minute (GPM).

- Based on your final equation, what is the single most effective way to *increase* the maximum flow rate *without* causing cavitation? (Assume you cannot change the fluid or atmospheric pressure).

Fundamentals of Hydraulics: Bernoulli & Cavitation

To solve this problem, we must relate the pressure, velocity, and elevation of the water at different points. This is done using two fundamental principles: conservation of energy (Bernoulli's Equation) and conservation of mass (Continuity Equation). We must also use absolute pressures to correctly identify the cavitation limit.

1. Bernoulli's Equation (Energy Head Form)

This equation describes the conservation of energy in an ideal (frictionless) fluid flow. It states that the total energy head (pressure head + elevation head + velocity head) is constant along a streamline.

\[ \frac{p_1}{\gamma} + z_1 + \frac{V_1^2}{2g} = \frac{p_2}{\gamma} + z_2 + \frac{V_2^2}{2g} + h_L \]

For this ideal exercise, we will assume head loss (\(h_L\)) is negligible (\(h_L = 0\)).

2. Continuity Equation (Mass Conservation)

For an incompressible fluid (like water), the volumetric flow rate (\(Q\)) must be constant. Therefore, the product of cross-sectional area (\(A\)) and average velocity (\(V\)) is constant.

\[ Q = A_1 V_1 = A_2 V_2 \]

This means if area decreases (like in our throat), velocity must increase.

3. Absolute Pressure & Cavitation Condition

Bernoulli's equation must use consistent pressure types. We will use absolute pressure.

\[ p_{abs} = p_{gage} + p_{atm} \]

Cavitation occurs when the *absolute* local pressure drops to or below the fluid's vapor pressure.

\[ p_{local, abs} \le p_v \]

Solution: Cavitation in a Venturi System

Question 1: Convert all parameters to consistent base units (feet, lb/ft², ft/s). Calculate the areas \(A_1\) and \(A_2\).

Principle

All calculations in physics and engineering must use a consistent set of base units. For US customary units in hydraulics, we use feet (ft) for length, pounds (lb) for force, and seconds (s) for time. This means pressure must be in pounds per square foot (psf) and area in square feet (ft²).

Mini-Lesson

The US Customary System (USCS) relies on the base units of feet (ft), pounds (lb), and seconds (s). Derived units, like pressure (\(p = F/A\)), must be expressed in these base units, which becomes lb/ft² (psf). This consistency is non-negotiable for equations like Bernoulli's, where terms are added together.

Pedagogical Note

Think of units as algebraic variables. The term \(p/\gamma\) must result in 'ft' of head. If \(p\) is in 'psi' (lb/in²) and \(\gamma\) is in 'lb/ft³', the units do not cancel. Converting 'psi' to 'psf' (lb/ft²) makes the math work: \( \frac{\text{lb/ft}^2}{\text{lb/ft}^3} = \text{ft} \). This is the goal.

Norms

Unit conversions follow standard US Customary definitions: 1 ft = 12 in. Therefore, 1 ft² = 12 in \(\times\) 12 in = 144 in².

Formula(s)

We will use the following conversion factors and formulas.

Pressure Conversion (psi to psf)

Diameter to Area (inches to ft²)

Hypotheses

We assume standard, exact definitions for the conversion factors.

Data

From the problem statement:

| Parameter | Symbol | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inlet DiameterThe diameter of the pipe at the wide section (Point 1). | \(D_1\) | 6 | in |

| Throat DiameterThe diameter of the pipe at the narrow, constricted section (Point 2). | \(D_2\) | 3 | in |

| Vapor Pressure | \(p_v\) | 0.363 | psi (abs) |

| Atmospheric Pressure | \(p_{atm}\) | 14.7 | psi (abs) |

Tips

The most common error in USCS hydraulics is forgetting to convert pressure from psi to psf. Since specific weight (\(\gamma\)) is in lb/ft³, the pressure term (\(p/\gamma\)) *must* have units of (lb/ft²) / (lb/ft³) to correctly result in feet (ft) of head. Always check your units!

Schematic (Before Calculations)

A schematic is not applicable for this unit conversion step. See the main schematic in the problem statement for the locations of \(D_1\) and \(D_2\).

Calculation(s)

We will convert each value from the problem statement into its base unit (feet, pounds, seconds).

Step 1: Convert Diameters (in) to Areas (ft²)

First, convert the diameters from inches to feet by dividing by 12. Then, use the area formula \(A = \pi D^2 / 4\).

We now have our two cross-sectional areas in square feet (ft²), which are ready for the continuity and Bernoulli equations.

Step 2: Convert Pressures (psi to psf)

To convert from pounds per square inch (psi) to pounds per square foot (psf), we multiply by 144 (since 1 ft² = 144 in²).

Both pressures are now in pounds per square foot (psf), which is dimensionally consistent with our specific weight unit (\(lb/ft^3\)).

Schematic (After Calculations)

A schematic is not applicable for this unit conversion step.

Analysis

The converted units (psf, ft²) are now dimensionally consistent with specific weight (lb/ft³) and gravity (ft/s²). This allows them to be used correctly in the Bernoulli equation, where all terms must resolve to units of feet (head).

Cautionary Points

Ensure that you use the radius, not diameter, if using the formula \(A = \pi r^2\). Using \(A = \pi D^2 / 4\) is often safer as diameters are usually given. Remember to divide the diameter in *inches* by 12 *before* squaring it.

Key Takeaways

- The base units for USCS hydraulics are feet (ft), pounds (lb), and seconds (s).

- Pressure *must* be converted from psi to psf (multiply by 144).

- Area *must* be converted from in² to ft² (divide by 144) or calculated from diameter in feet.

Did You Know?

The 'slug' is the official unit of mass in the USCS system, where 1 lb of force accelerates 1 slug at 1 ft/s². We use specific weight (\(\gamma\), in lb/ft³) to bypass the need for slugs in most fluid dynamics problems by working with weight (\(F=mg\)) directly.

FAQ

[List common follow-up questions students might have.]

Final Result

- Inlet Area (\(A_1\)): \(0.1963 \text{ ft}^2\)

- Throat Area (\(A_2\)): \(0.0491 \text{ ft}^2\)

- Vapor Pressure (\(p_v\)): \(52.27 \text{ psf}\) (absolute)

- Atmospheric Pressure (\(p_{atm}\)): \(2116.8 \text{ psf}\) (absolute)

Your Turn

If a new inlet pipe had a diameter of 4 inches, what would its area be in ft²?

Memo Card

Question 1 Summary:

- Key Concept: Unit Consistency

- Essential Formula: \(p \text{ (psf)} = p \text{ (psi)} \times 144\)

- Key Data: \(A = \pi (D \text{ [ft]})^2 / 4\)

Question 2: State the Continuity Equation (relating \(V_1\) and \(V_2\)) and the full Bernoulli's equation (in head form) that will be used.

Principle

We must state the two governing physical laws for this problem: conservation of mass (which gives us the Continuity Equation) and conservation of energy (which gives us Bernoulli's Equation).

Mini-Lesson

The Continuity Equation (\(Q=AV\)) allows us to relate the velocities at two different points based on their areas. Bernoulli's Equation (\(\frac{p}{\gamma} + z + \frac{V^2}{2g} = \text{const}\)) allows us to relate the energy (as pressure, elevation, and velocity) between those same two points.

Pedagogical Note

These two equations are the foundation of most incompressible flow problems. Continuity links the *kinematics* (motion) of the flow, while Bernoulli links the *dynamics* (energy and forces) of the flow.

Norms

These are idealized physical laws, assuming an incompressible (density is constant) and inviscid (frictionless) fluid in steady flow.

Formula(s)

The two equations are:

Continuity Equation

Bernoulli's Equation (Ideal, no head loss)

Hypotheses

We assume:

- The fluid (water) is incompressible (\(\rho\) is constant).

- The flow is steady (velocity and pressure at a point do not change over time).

- The flow is frictionless (inviscid), so head loss \(h_L = 0\).

Data

From Q1, we know the area ratio:

- \(A_1 = 0.1963 \text{ ft}^2\)

- \(A_2 = 0.0491 \text{ ft}^2\)

- Ratio \(A_1 / A_2 \approx 4\), or \(A_2 / A_1 \approx 0.25\)

Tips

Always write the full Bernoulli equation first, then simplify by crossing out terms (like \(z_1=z_2\) for horizontal flow, or \(V_1 \approx 0\) for a large reservoir). This prevents errors of omission.

Schematic (Before Calculations)

A schematic is not applicable for this step, as we are only stating the equations.

Calculation(s)

No new calculations are needed for this step. We are stating the governing equations. However, we can pre-calculate the relationship between \(V_1\) and \(V_2\) using our new area values.

From the Continuity Equation \(A_1 V_1 = A_2 V_2\), we can isolate \(V_1\):

This shows the velocity in the inlet pipe is 1/4 of the velocity in the throat, which makes sense as the area is 4 times larger.

Schematic (After Calculations)

Not applicable.

Analysis

The continuity equation confirms that the velocity at the inlet (\(V_1\)) will be 1/4 of the velocity at the throat (\(V_2\)). This is a key relationship. The Bernoulli equation shows that to achieve this high \(V_2\), energy must be converted from pressure head (\(p/\gamma\)) or elevation head (\(z\)).

Cautionary Points

Do not confuse the two equations. Continuity (\(AV\)) relates velocity and area. Bernoulli relates velocity, pressure, and elevation. You often need to use Continuity *inside* the Bernoulli equation (by substituting for \(V_1\)) to solve for a single unknown velocity.

Key Takeaways

- Continuity: Small Area = High Velocity.

- Bernoulli: High Velocity = Low Pressure (if elevation is constant).

- These two principles are almost always used together.

Did You Know?

The Venturi effect, described by these equations, is how carburetor engines mix air and fuel, and how many paint sprayers work. The high-velocity air in the throat creates a low-pressure zone that siphons the liquid (fuel or paint) into the stream.

FAQ

[List common follow-up questions students might have.]

Final Result

Your Turn

From Q1, our area ratio \(A_1/A_2\) is \(0.1963 / 0.0491 \approx 4\). If the throat velocity \(V_2\) is 20 ft/s, what is the inlet velocity \(V_1\) in ft/s?

Memo Card

Question 2 Summary:

- Key Concept: Conservation of Mass & Energy.

- Formula 1: \(A_1 V_1 = A_2 V_2\)

- Formula 2: \(\frac{p_1}{\gamma} + z_1 + \frac{V_1^2}{2g} = \frac{p_2}{\gamma} + z_2 + \frac{V_2^2}{2g}\)

Question 3: Apply Bernoulli's equation between the reservoir surface (Point 1) and the throat (Point 2) to find the throat velocity (\(V_2\)) at the onset of cavitation.

Principle

We will apply the Bernoulli equation from the reservoir surface (Point 1) to the throat (Point 2). We set the pressure at Point 2 to the vapor pressure (\(p_v\)), which is the physical limit for cavitation. We can then solve for the velocity, \(V_2\).

Mini-Lesson

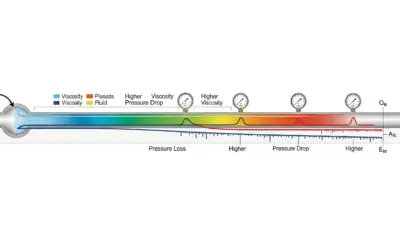

The total energy at the reservoir surface (potential energy from elevation \(z_1\) and pressure \(p_{atm}\)) is converted into energy at the throat. At the cavitation limit, this energy is the sum of the velocity energy (\(V_2^2/2g\)) and the minimum possible pressure energy, which is the vapor pressure head (\(p_v/\gamma\)).

Pedagogical Note

This is the core of the problem. We are defining the *total available energy* at the start (Point 1) and setting it equal to the *energy required* at the end (Point 2). The "required" energy is the energy to keep the liquid from boiling (\(p_v\)) plus the energy of its motion (\(V_2\)).

Norms

The cavitation condition is a physical limit: \(p_{local, abs} \ge p_v\). We are solving for the boundary condition where \(p_2 = p_v\).

Formula(s)

We start with our simplified Bernoulli's equation and solve for \(V_2\).

Solved for \(V_2\):

Hypotheses

To simplify Bernoulli's equation, we make the following critical assumptions:

- At Point 1 (Reservoir Surface):

- It's a "large reservoir," so the velocity of the water surface is negligible: \(V_1 \approx 0\).

- The reservoir is "open to the atmosphere," so the gage pressure is 0, and the absolute pressure is \(p_1 = p_{atm}\).

- The elevation is given: \(z_1 = 20 \text{ ft}\).

- At Point 2 (Throat):

- We are at the "onset of cavitation," so the absolute pressure is the vapor pressure: \(p_2 = p_v\).

- The elevation is the datum: \(z_2 = 0 \text{ ft}\).

- The velocity \(V_2\) is our unknown.

- We assume an ideal system with no friction or head loss (\(h_L = 0\)).

Data

From Q1 and the problem statement:

| Parameter | Symbol | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pressure at 1 | \(p_1 = p_{atm}\) | 2116.8 | psf (abs) |

| Elevation at 1 | \(z_1\) | 20 | ft |

| Velocity at 1 | \(V_1\) | 0 | ft/s |

| Pressure at 2 | \(p_2 = p_v\) | 52.27 | psf (abs) |

| Elevation at 2 | \(z_2\) | 0 | ft |

| Specific Weight | \(\gamma\) | 62.3 | lb/ft³ |

| Gravity | \(g\) | 32.2 | ft/s² |

Tips

The biggest trap is using *gage* pressure. \(p_1\) is \(p_{atm}\) (absolute), so \(p_2\) *must* also be absolute (\(p_v\)). You cannot mix gage and absolute pressures in the same equation. Also, notice we did not need \(A_1\) or \(A_2\) *yet* because we assumed \(V_1 \approx 0\). This is a very common and powerful simplification.

Schematic (Before Calculations)

Refer to the main system schematic. We are applying Bernoulli's equation from the water surface (Point 1) to the center of the throat (Point 2).

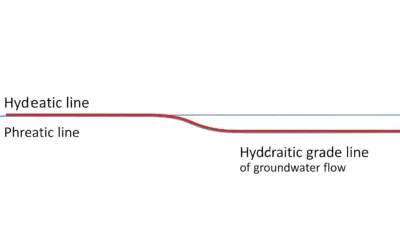

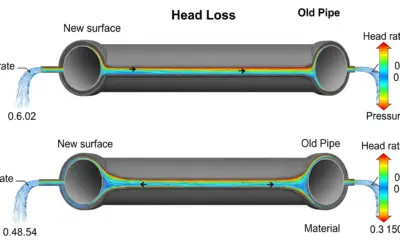

EGL and HGL for Cavitation Analysis

Calculation(s)

We will substitute our known values into the Bernoulli equation, step-by-step, to solve for \(V_2\).

Step 1: Write the Simplified Bernoulli Equation

From our hypotheses (\(V_1=0, z_2=0, p_1=p_{atm}, p_2=p_v\)), the equation becomes:

This equation states that the total energy at the reservoir (left side) is converted into the energy at the throat (right side) at the point of cavitation.

Step 2: Calculate the Head Terms (in feet)

We first calculate the value of each 'head' term (pressure head and elevation head) using the values from Q1 and the problem statement.

This shows the total energy available from the atmosphere is 34.0 ft of head, the elevation provides 20.0 ft, and the minimum pressure allowed at the throat "costs" 0.84 ft of head.

Step 3: Substitute Head Values into the Equation

Now we plug these numbers back into the simplified equation from Step 1.

The total available head is 54.0 ft. This must be equal to the vapor pressure head (0.84 ft) plus the velocity head (\(V_2^2/64.4\)) at the throat.

Step 4: Solve for \(V_2\)

Finally, we isolate \(V_2\) algebraically.

The resulting value, 58.51 ft/s, is the maximum velocity the water can reach in the throat before the pressure drops to the vapor pressure and cavitation begins.

Schematic (After Calculations)

The EGL/HGL schematic shown above is the result. The total energy head (EGL) is constant at \(34.0 + 20 = 54.0 \text{ ft}\). The HGL drops to the vapor pressure head (\(0.84 \text{ ft}\)) at the throat. The difference, \(54.0 - 0.84 = 53.16 \text{ ft}\), is the velocity head \(V_2^2/2g\), which matches our calculation.

Analysis

The maximum possible velocity in the throat, before the water starts to boil (cavitate), is 58.51 ft/s. If the flow is forced to go any faster (e.g., by opening a valve further downstream), the pressure would *need* to drop below \(p_v\), and the system would cavitate violently.

Cautionary Points

This calculation is for an *ideal* system. In reality, friction losses (\(h_L\)) would consume some of the energy, so the *actual* maximum velocity would be slightly lower. We would subtract \(h_L\) from the left side of the equation: \(\frac{V_2^2}{2g} = \left( \frac{p_{atm}}{\gamma} + z_1 \right) - \frac{p_v}{\gamma} - h_L\).

Key Takeaways

- The total energy head of the system is set by the reservoir: \(H_{total} = p_{atm}/\gamma + z_1\).

- The cavitation limit at the throat is set by \(p_2 = p_v\).

- The available energy head (\(H_{total} - p_v/\gamma\)) is converted entirely into velocity head (\(V_2^2/2g\)) in an ideal case.

Did You Know?

Cavitation damage is not from the bubbles themselves, but from their *collapse*. When a vapor bubble flows into a higher-pressure region (downstream of the throat), it implodes violently. This collapse creates a micro-jet of water and a shockwave that can exceed 100,000 psi, pitting and destroying metal components like pump impellers and propellers.

FAQ

[List common follow-up questions students might have.]

Final Result

Your Turn

What would the max throat velocity \(V_2\) be if the reservoir was raised to 30 ft (\(z_1 = 30\))? (All other data is the same, assume \(V_1 \approx 0\)).

Memo Card

Question 3 Summary:

- Key Concept: Energy Conversion.

- Essential Formula: \(H_{total} = H_{velocity} + H_{pressure}\)

- Key Data: \(p_2 = p_v\) at cavitation.

Question 4: Calculate the volumetric flow rate (\(Q\)) in cubic feet per second (cfs). Then, convert this flow rate to gallons per minute (GPM).

Principle

Now that we have the maximum velocity at the throat (\(V_2\)) and the area of the throat (\(A_2\)), we can use the Continuity Equation to find the maximum flow rate (\(Q\)). We then use a standard conversion factor to find GPM.

Mini-Lesson

Volumetric flow rate, \(Q\), is the volume of fluid passing a point per unit time. It is calculated as \(Q = A \times V\). Since \(A_2\) and \(V_2\) are known, we can find \(Q\). This \(Q\) is the same at Point 1 and Point 2 (and everywhere else in the pipe).

Pedagogical Note

This step connects the *velocity* (an energy component) back to the *flow rate* (a system performance metric). Engineers are usually most interested in the flow rate (GPM) a system can deliver. Our calculation finds the *maximum* GPM before the system is damaged by cavitation.

Norms

The US standard conversion factor for cfs to GPM is a defined value. 1 ft³ \(\approx\) 7.48052 gallons. 1 minute = 60 seconds. (7.48052 \(\times\) 60 \(\approx\) 448.83).

Formula(s)

We use the continuity equation and the conversion factor for cfs to GPM.

Flow Rate Equation

Conversion Factor

Hypotheses

We assume the velocity \(V_2\) is uniform across the cross-sectional area \(A_2\), which is a standard assumption for this level of problem (we are using the *average* velocity).

Data

From Q1 and Q3:

- Throat Area (\(A_2\)): \(0.0491 \text{ ft}^2\)

- Throat Velocity (\(V_2\)): \(58.51 \text{ ft/s}\)

Tips

The conversion 1 cfs \(\approx\) 449 GPM is one of the most common in US water systems. Memorizing it is very helpful for quick estimations.

Schematic (Before Calculations)

Not applicable. This is a direct calculation.

Calculation(s)

We will use the throat velocity (\(V_2\)) and throat area (\(A_2\)) from the previous steps to find the flow rate (\(Q\)).

Step 1: Calculate Flow Rate in cfs (Cubic Feet per Second)

We apply the continuity equation formula: \(Q = A \times V\), using the values for the throat (Point 2).

The units are correct: \(\text{ft}^2 \times \text{ft/s} = \text{ft}^3/\text{s}\), or cfs.

Step 2: Convert cfs to GPM (Gallons Per Minute)

We use the standard conversion factor \(1 \text{ cfs} = 448.83 \text{ GPM}\).

This is the flow rate in the standard unit used for pumping and water distribution in the US.

Schematic (After Calculations)

Not applicable.

Analysis

The maximum flow rate this Venturi system can handle under these conditions is 2.87 cfs, or just under 1300 GPM. If a pump or valve tries to pull more water than this, the system will cavitate at the throat.

Cautionary Points

Be sure to use the area and velocity from the *same point* to calculate Q. We could have also used \(V_1 = V_2 / 4 = 14.63 \text{ ft/s}\) and \(A_1 = 0.1963 \text{ ft}^2\). The result is the same: \(Q = A_1 V_1 = 0.1963 \times 14.63 = 2.873 \text{ cfs}\). This is a good way to check your work.

Key Takeaways

- Flow rate \(Q\) is constant throughout the pipe.

- \(Q = A \times V\).

- 1 cfs \(\approx\) 449 GPM.

Did You Know?

Large municipal water pumps can move over 100,000 GPM. Designing the pump inlets (the "suction" side) to avoid cavitation is one of the most critical tasks for hydraulic engineers, as a cavitating pump can be destroyed in a matter of hours.

FAQ

[List common follow-up questions students might have.]

Final Result

Your Turn

If the maximum allowed velocity \(V_2\) was only 50 ft/s, what would the flow rate \(Q\) be in cfs? (Use \(A_2 = 0.0491 \text{ ft}^2\)).

Memo Card

Question 4 Summary:

- Key Concept: Flow Rate Calculation.

- Essential Formula: \(Q = A_2 V_2\)

- Key Data: \(1 \text{ cfs} = 448.83 \text{ GPM}\)

Question 5: Based on your calculations, what is the single most effective way to *increase* the maximum flow rate *without* causing cavitation? (Assume you cannot change the fluid or atmospheric pressure).

Principle

This is a synthesis question. The flow rate is \(Q = A_2 V_2\). To increase \(Q\), we must increase \(A_2\) or \(V_2\). We must analyze the Bernoulli equation from Q3 to see how our controllable variables affect these terms.

Mini-Lesson

System performance is limited by the available energy. The total energy head (driving the flow) is \(H_{total} = (p_{atm}/\gamma + z_1)\). The required energy head (to prevent boiling) is \(H_{required} = p_v/\gamma\). The leftover energy becomes velocity head: \(V_2^2/2g = H_{total} - H_{required}\). To increase \(V_2\), we must increase \(H_{total}\).

Pedagogical Note

This question checks your understanding of the *relationships* in the Bernoulli equation. \(V_2\) is driven by the total available head. Since we cannot change \(p_{atm}\) or the fluid (\(p_v, \gamma\)), the only term in the total head we *can* change is \(z_1\).

Norms

This is a conceptual analysis of the governing equations.

Formula(s)

We analyze the two key equations:

Hypotheses

We assume we are system operators/designers and can change the geometry (\(A_2\)) or the initial setup (\(z_1\)). We assume we cannot change physics (\(g\)), the weather (\(p_{atm}\)), or the fluid properties (\(\gamma, p_v\)).

Data

Not a numerical calculation, but a conceptual analysis of the relationships in the formulas from Q3 and Q4.

Tips

Look at the equations. How can you make \(Q\) bigger?

1. Make \(A_2\) bigger. This is a design change (widen the throat).

2. Make \(V_2\) bigger. How? Look at the \(V_2\) formula. The only variable we can change is \(z_1\). Making \(z_1\) (elevation) bigger makes \(V_2\) bigger.

Schematic (Before Calculations)

Not applicable.

Calculation(s)

This is a conceptual analysis of the formulas, not a new calculation. We are inspecting the variables in our two main equations:

Equation 1: Flow Rate

This equation tells us how flow rate (\(Q\)) is calculated. To get more flow, we need a bigger area (\(A_2\)) or a faster velocity (\(V_2\)).

Equation 2: Max Velocity

This equation, derived from Bernoulli, tells us what controls the maximum possible velocity (\(V_2\)).

To increase \(Q\), we must increase \(A_2\) (a design change) or increase \(V_{2,max}\). To increase \(V_{2,max}\), we look at its equation. Since \(p_{atm}\), \(\gamma\), and \(p_v\) are fixed, the only "knob" we can turn is \(z_1\). Increasing \(z_1\) (reservoir elevation) increases the total energy, which increases the maximum possible \(V_2\).

Schematic (After Calculations)

Not applicable.

Analysis

From our formula, \(Q = A_2 \times V_2\).

Both are valid, but "raise the reservoir elevation" is the most direct answer based on the variables in the energy equation.

Cautionary Points

Don't just say "increase \(V_2\)". \(V_2\) is a *result* of the system's energy, not an *input*. The "knob" we can turn is \(z_1\). Turning the \(z_1\) knob "up" makes the \(V_2\) "dial" go up.

Key Takeaways

- The maximum flow rate is limited by the total energy head (\(p_{atm}/\gamma + z_1\)).

- To increase the max flow rate, you must either increase the total energy head (by raising \(z_1\)) or change the design (widen \(A_2\)).

Did You Know?

This is why water towers are tall. The height (\(z_1\)) of the water in the tower provides the pressure (head) for the entire water distribution system, pushing water to homes and fire hydrants without needing pumps (in a simple gravity-fed system).

FAQ

[List common follow-up questions students might have.]

Final Result

Your Turn

If we used a *smaller* throat (decrease \(D_2\)), would the maximum *flow rate (Q)* before cavitation increase or decrease? (Enter 1 for increase, 0 for decrease). (Hint: \(Q = A_2 V_2\). \(V_2\) is fixed by \(z_1\). What happens to \(Q\) if \(A_2\) gets smaller?)

Memo Card

Question 5 Summary:

- Key Concept: System Optimization.

- Essential Formula: \(Q \propto A_2 \times \sqrt{z_1 + \text{const.}}\)

- Key Data: Increasing \(z_1\) increases \(V_{2,max}\).

Interactive Tool: Cavitation Velocity Calculator

Use the sliders to see how changing the reservoir elevation (\(z_1\)) and water temperature (which changes \(p_v\)) affects the maximum allowable throat velocity (\(V_2\)).

Input Parameters

Key Requirements

Final Quiz: Test Your Knowledge

1. Which of the following best describes cavitation?

2. In a horizontal Venturi pipe with flowing water, where is the static pressure the *lowest*?

3. According to Bernoulli's principle (assuming constant elevation), if the fluid velocity *increases*, what happens to its static pressure?

Glossary

- Bernoulli's Equation

- A statement of the conservation of energy for an ideal (frictionless) fluid flow. It relates the pressure head, elevation head, and velocity head between two points on a streamline.

- Cavitation

- A phenomenon where vapor bubbles form in a liquid when the local absolute pressure drops to or below the liquid's vapor pressure. The subsequent collapse (implosion) of these bubbles in higher-pressure zones can cause significant noise, vibration, and erosion damage.

- Continuity Equation

- A statement of the conservation of mass for an incompressible fluid. It dictates that the volumetric flow rate (\(Q = A \times V\)) is constant in a closed system.

- Head

- A way to express energy in a fluid system in terms of an equivalent height of fluid (e.g., "feet of head"). Pressure head is \(p/\gamma\), velocity head is \(V^2/2g\), and elevation head is \(z\).

- Vapor Pressure (\(p_v\))

- The pressure at which a liquid will boil (turn into a gas or "vapor") at a given temperature. This is the critical pressure floor for cavitation.

- US Customary Units (USCS)

- The system of measurement commonly used in the United States, based on feet (ft), pounds (lb), and seconds (s). Pressure is often in pounds per square inch (psi) or pounds per square foot (psf).

0 Comments